July 5, 2024

National Museum of Ethnology: Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Museum’s Founding

Kenji Yoshida

Director-General

National Museum of Ethnology

Minpaku Celebrates Its 50th Anniversary

The National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) celebrates its 50th anniversary this year in 2024.

Minpaku was founded on the 7th of June 1974 under the “Law to Amend Part of the National School Establishment Law” as an Inter-University Research Institute in Ethnology / Cultural Anthropology and related fields. Subsequently, the museum opened its doors to the public in November 1977 after the main building was completed on the site of the 1970 Osaka Expo in Senri, Osaka. In 1989, the School of Cultural and Social Studies of the Graduate University for Advanced Studies (SOKENDAI) was established within the museum. Since 2004, under the implementation of the National University Corporation Act, the museum has become a constituent organization of the National Institute for the Humanities (Figure 1).

Due to this particular type of founding, Minpaku, despite bearing the name “National Museum of Ethnology,” primarily operates as a research institution equipped with a museum that accumulates research materials and disseminates the results of research activities. Simultaneously, it also fulfills the educational role of a graduate school, making it a highly unique institution on an international scale. Because of this form of establishment, Minpaku does not have curators or a curatorial department. Researchers at Minpaku engage in their respective research and educational activities concurrently with museum activities under the positions of professor, associate professor, and assistant professor.

For over 45 years, I have dedicated myself to anthropological fieldwork in Africa. In particular, my life’s work focuses on studying masks and masquerading. Since 1984, I have been conducting fieldwork on the Nyau mask society among the Chewa people in Zambia, Southern Africa.

The mask society is composed exclusively of men, and the dancers who appear in rituals, especially funeral rites, are considered embodiments of the deceased. The fact that humans wear masks is kept secret from women and children who are not members of society (Figure 2). For this reason, I was unable to join the society and continued to receive the same treatment as the women and children for over a year. During that period, after I settled down in the village called Kaliza, I could only cultivate the fields lent to me by the villagers. On May 25, 1985, I was allowed to become a member of the society after receiving the rite of initiation. Since then, I have returned to the village almost every year to continue my surveys and research as a member of the society.

Then, from 1990 to 1991, I had an opportunity to stay in London as a visiting researcher at the British Museum. Encountering the museum’s vast collection, I pondered why humans collect things. Since then, another pillar of my research has become the formation of museums and their collections and the representation of culture through those collections [Yoshida, 2016].

At the moment, fifty-five researchers at Minpaku, including myself, engage in fieldwork in various locations worldwide, researching the diversity and commonalities of human cultures and societal dynamics. Currently, Minpaku is the only institution in the world that serves as both a research and educational institution in cultural anthropology, with researchers and research organizations spanning the entire globe, alongside extensive collections and exhibition facilities encompassing worldwide representation.

Over 346000 objects have been collected at Minpaqku, constituting the world’s most extensive ethnographic collection after the second half of the 20th century. At the same time, regarding the scale of its facilities, Minpaku is currently the largest ethnological museum in the world (Figure 3).

Museums at the Turning Point of Civilization

Human civilization today is facing the most significant turning point in several centuries. Until recently, the group regarded as central ruled and controlled unilaterally the group regarded as peripheral. The dynamics of this power relationship seem to be changing now. These days, we witness that contacts, interactions, and amalgamation, including the creative and the destructive, are occurring worldwide in a bilateral manner between those two entities; one used to be regarded as central and the other peripheral. New global divides are emerging amid this movement.

On the other hand, since experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, we have realized that human life is closely intertwined with the movements of invisible viruses and bacteria. In other words, we have experienced firsthand that humanity is also a member of the “biosphere” that encompasses all life forms. Furthermore, terms such as “the Anthropocene” have been coined to describe this era, leading to an awareness that human activities exert irreversible burdens on the Earth’s environment, with the urgent need for global responses with consideration towards the future.

Thus, despite humanity’s need to work collectively, the current situation is marked by challenges that hinder such cooperation. Consequently, there is an unprecedented need to build a world where people can live together beyond language and cultural differences while respecting diverse cultures. Currently, more than ever, anthropological knowledge and ethnological museums that deepen the understanding of each other’s culture based on empathy are required.

Marking 50 years since our foundation, we have decided to conduct a series of projects to commemorate our anniversary by reflecting on the past 50 years, evaluating our current state, and envision the future of Minpaku for the next 50 and 100 years. Specifically, we plan to compile and publish a “50-year history of Minpaku,” establish “Museum Archives” which consists of interviews with honorary professors under the title “Testimonies of the Era,” hold 50th-anniversary special exhibitions, and host a series of 50th-anniversary international symposiums aimed at envisioning the future.

Alongside global changes, the landscape surrounding museums has undergone a significant transformation over the last half-century. A reevaluation of the traditional approach of museums, which have unilaterally presented fixed information and representations grounded in scientific and universal values, is currently taking place in various places. A variety of trials are conducted at museums, such as museum activities rooted in community and resident participation, collaborating with educational institutions, promoting the process of collecting and exhibiting premised on collaboration between those who are collecting/exhibiting and those who are collected/exhibited, and creating a shared database to input and utilize information about the materials in the collection with the public. In recent years, there has been a rise in movements resembling “competitions” for the repatriation of cultural heritages taken from localities during the colonial era, aiming to return them to their original places from Europe and America.

In either case, we can observe a shift in the role of museums, which used to be unilateral instruments for disseminating information. Now, they are being resurrected as generators of interactive and multidirectional exchanges and the flow of information. We can observe a clear image taking shape regarding the future of museums, particularly with regard to the communities or societies that initially produced the items now housed in the museums. Rather than being the collection’s final owners, museums are instead “custodians,” which facilitates various collaborative activities with the original owners or users.

Museums as a Forum

In terms of collaborative efforts with the original owners of the collections, since 1978, when the permanent exhibition of Ainu culture first opened to the public at Minpaku, we have since annually invited members from various districts of the Hokkaido Ainu Association to take turns to host the Kamuinomi ritual. In the Ainu worldview, every aspect of existence, including animals, plants, dwellings, and objects, is believed to be imbued with a spiritual presence called “Kamui.” The Kamuinomi ritual at Minpaku is a ceremony to pray for the safe preservation of Ainu materials stored at Minpaku and their inheritance to the next generation. During the ritual, utensils and tools typically kept in storage are used. Each time I partake in this ritual, I feel that it is a moment when the Ainu artifacts and Minpaku itself are imbued with fresh life. (Figure 4).

An Approach of the Info-Forum Museum: To Create a Source Community-driven Multivocal Museum Catalog. Trajectoria: Anthropology, Museums and Art. Vol.1 2020.

As evidenced by this collaborative effort with the Ainu people, Minpaku has long positioned itself as a “forum” for interaction, collaboration, and co-creation among three parties: museum researchers, visitors, and people of local communities who originally produced the materials housed and displayed in the museum.

Since commencing in 2009, the recently completed full-scale renovation of the permanent exhibition in the main building has been based on collaborative planning and production with individuals from the respective regions that each gallery represents, such as Oceania and Africa. The process genuinely realized the concept of the “museum as a forum” (Figure 5).

In the 1970s, art historian Duncan Cameron, who was then the director of the Brooklyn Museum, pointed out that museums have two distinct roles: “temple” and “forum” [Cameron 1974]. Here, “temple” refers to a place like a shrine where people come to worship already established “treasures,” while the museum as a “forum” means a place where people gather, encounter unknown things, and begin discussions and new challenges.

I first introduced this concept at a symposium that marked the 20th Anniversary of Minpaku’s opening, “21st Century Ethnology and Museums: A New Approach to Presenting Other Cultures” in 1994. Since then, this concept of the “museum as a forum” has been widely embraced within Minpaku, defining Minpaku itself as a “forum” for wisdom, as mentioned earlier. The concept has also gained extensive support among museums worldwide and sparked significant momentum [Yoshida 1999, 2014].

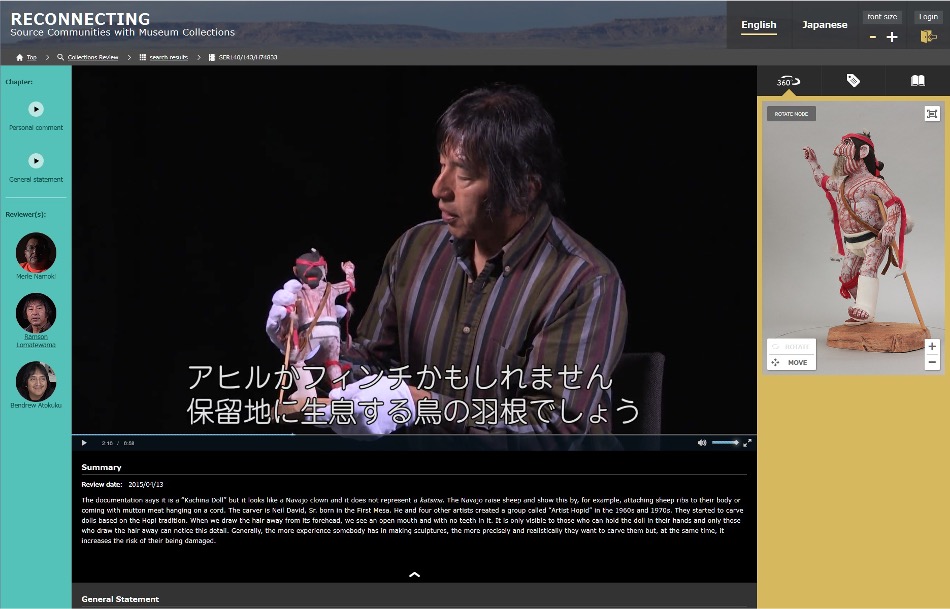

At Minpaku, we have been working on a project titled “Info-Forum Archives of Human Cultures.” This project aims to share information about Minpaku’s artifacts, photographs, and other audio-visual materials not only with researchers and museum visitors from Japan and worldwide but also with the members of society that initially produced these materials or, in the case of photographs and videos, with the local communities where they were taken. We strive to store this shared information in a database that can be accessed internationally and developed to facilitate fresh collaborative research, joint exhibitions, and even new community activities.

Activities such as bringing objects back to their origin for an exhibition of returned works are also being carried out in Taiwan and Korea. Sometimes, local residents are invited to Minpaku to provide additional information to our database (Figure 6). In cases where visiting Minpaku in person is difficult, workshops are held locally. Images of objects from Minpaku’s collection database are projected onto screens individually, and local opinions about the object are gathered.

An Approach of the Info-Forum Museum: To Create a Source Community-driven Multivocal Museum Catalog. Trajectoria: Anthropology, Museums and Art. Vol.1 2020.

In either case, the information we gather extends beyond the mere name and usage of the items, but also personal memories and individual experiences associated with them. These narratives are recorded in video format and incorporated into the database. When photographs or videos taken in the past are brought back to the local community, there are moments when people excitedly exclaim, “Oh, that’s my grandmother!” or “That’s my grandfather!”. At the same time, some even shed tears of joy. The individuals cooperating in this project often express that their involvement goes beyond merely enriching Minpaku’s data archives. They also wish to preserve their experiences and memories here and pass them on to future generations, including grandchildren or great-grandchildren they may never meet. The database was created this way, covering regions worldwide, with over 40 entries already. Ultimately, Minpaku has become a platform for storing and transmitting human memories.

These activities can contribute to Minpaku’s long-standing goal of establishing itself as a “museum as a forum” for intellectual exchange and collaborative creation among diverse individuals. This goal extends beyond museum exhibitions, including accumulating material information and even anthropological research activities.

As we celebrate the significant milestone of 50 years since our foundation, we are looking ahead to the next 50 years and beyond, aiming to enhance our role as a “forum” and particularly as a platform for preserving human memory and co-creating the future based on it. We are committed to expanding our activities to explore guidelines for realizing a convivial human society.

We sincerely appreciate your continued guidance and support.

<References>

Cameron, Duncan

1971 The Museum: a Temple or the Forum’. Journal of World History, 14:11-21.

Yoshida, Kenji

’Discovery’ of Culture: From a Room of Wonders to a Virtual Museum, Iwanami Shoten, 1999

’Discovery’ of Culture: From a Room of Wonders to a Virtual Museum, Iwanami Human Culture Selection, Iwanami Shoten, 2014

Exploring the World of Masks: The Exchange Between Africa and Museums, Rinsen Book Co., 2016