February 8, 2023

Pioneering “Virtual” Possibilities for the Dissemination of Ethnic Culture

Gaoli Liu

Associate Fellow, National Ainu Museum

Visiting Researcher, National Museum of Ethnology

Residing in the Exhibition Planning Division, Research and Curatorial Department of the National Ainu Museum, I am in charge of the multilingualization of exhibitions, the audiovisual integration, and the virtual museum project. In this article, I will examine the practice of “virtualization” in ethnographic museum exhibitions and the possibilities of “virtualization” by citing actual examples of the production of the Virtual National Ainu Museum. I would like to share my experiences and thoughts as a museum professional.

Initial Thoughts —— The Unexpected “Virtual” Operations and its Examination

In July 2020, as the effects of the novel coronavirus spread around the world, Japan’s northernmost national museum, National Ainu Museum, opened its doors. This museum is the core facility of Upopoy (National Ainu Museum and Park) and is the second national museum centered around ethnology in Japan. Unlike the National Museum of Ethnology, which opened in Osaka in the 1970s to exhibit and research the ethnic cultures of various regions of the world, this museum specializes in the research and the display of the Ainu culture. Its mission is “to promote respect for the Ainu as an indigenous people in Japan, to establish proper recognition and understanding of Ainu history and culture both nationally and internationally, and to contribute to the creation and development of new Ainu culture.”

Shiraoi Town, Hokkaido, where the museum is located, is rich in nature and has long been home to Ainu people. I encounter things important to the Ainu culture on my commute almost every day. Ezo red fox and Yezo sika deer run along the roads daily, and, though rarely, brown bears are sighted around my home. For the museum’s researchers who have been studying Ainu culture and history for many years, it is an idyllic environment as if living inside a “fieldwork” of their research expertise. However, some aspects of technology that have been integrated into every crevice of urban cities have yet to reach this area. For example, the installation of WIFI for home use is so rare that the road in front of my house was temporarily closed for full-scale construction when it was installed. The escalator at the museum became the first one installed in Shiraoi Town and became a shining beacon of pride for the museum.

In an environment such as this, in May 2021, 10 months after the museum’s opening, we were tasked with creating a “virtual museum” using advanced VR technology to disseminate information on Ainu culture in response to the “new normal” caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. When the study team was assembled, we immediately faced various concerns from both academic and technological perspectives, such as “what is a virtual museum,” “where should we begin,” “where is the demand,” “would the different aspects of the extraordinary, technological, and natural ethnic culture clash when they are conglomerated?”

The basic concept at the time was to create something that would allow visitors to experience the museum’s atmosphere at home, using the National Museum of Nature and Science’s “Kahaku VR” model. Accordingly, a contractor was selected through a bidding process that could utilize a 3D camera and the 3D modeling services of Matterport, a leading company specializing in digital twin. By the end of November, 3D photography of the entire museum was completed. Thus, the work was underway.

A Renewed Understanding —— What is “Virtual?”

In early December, we planned to create a 3D model while simultaneously compiling the contents of the central and sub-themes and explanatory texts of the museum’s exhibition rooms, written in eight languages, including Ainu, and inserting them into the 3D model. However, just before the launch, we were unexpectedly confronted with the fundamental question of what is a “virtual museum.” The Ainu language authors of the exhibition room descriptions were experts in their respective Ainu dialects, and their penned contributions could only be used within the exhibition rooms of the National Ainu Museum. The question arose as to whether the “virtual museum,” so to speak, an “exhibition room” that reproduced the real museum on the Internet in the form of a 3D model, could be called an “exhibition room of the National Ainu Museum.”

Therefore, the staff in charge of the Ainu language confirmed with each author of the Ainu language texts and obtain consent from everyone by February 2022. All the while, the staff was asked by the authors – what is a “virtual museum?”

The English word “virtual” has been translated into Japanese as “(not on the surface or nominally) factual, substantial, actual, imaginary,”[i] or “That which is not an entity or fact but indicates the essence of the substance. Temporary, virtual, false, imaginary.”[ii] It is an abstract meaning with a wide range of indications. “VR” technology is a term coined to unify the dichotomy between “virtual” and “reality” and is within the scope of engineering research. According to the definition by the Virtual Reality Society of Japan, virtual reality is characterized by “a natural three-dimensional space that is composed by humans,” “humans can act freely in it while interacting with the environment in real-time,” and “the environment and the humans create a seamless state of being within the environment.” In other words, the three essential elements are “three-dimensional spatiality,” “real-time interaction,” and “self-projection.”[iii] Also, wearing VR goggles to view and experience 3D content is the prevalent VR experience.

Comparing the definitions of “virtual” and “virtual reality,” the meaning of “virtual museum” became increasingly ambiguous. Perhaps one of the emergency responses to the pandemic was to rely on the technology of Matterport to make the museum available to those who could not visit and to make the museum itself available online as a “virtual image.” The use of new technologies, such as full-fledged “virtual reality,” needs further considerations to create new experiences and knowledge through the interaction between humans and the environment.

Reconsidering —— Opening the Path

As I mentioned above, clearing the conceptions surrounding “virtual” made me more open-minded, and my perception of the production of a “virtual museum” changed completely.

It is essential to express the essence, not the substance, as a form. 3D modeling by Matterport was used to create the “form” of the entire museum. However, we began to think that it would be important not to limit ourselves to that form but to create a space that is inclusive and transcends language and cultural barriers and physical disabilities. In this way, more people can appreciate the museum in order to communicate its philosophy and disseminate the Ainu culture.

With this in mind, we decided to focus not only on the online “visual” experience, but also on the “auditory” one.

First, without Matterport’s 3D modeling, we developed an automatic audio guide course that works with other software and embedded it in the pages of the virtual museum. The audio content is an overview of the exhibition rooms and its primary purpose, explained by the curator in charge.

We also wanted the voices of the museum’s conservation specialists, who are the “doctors” of the collection, constantly maintaining the museum’s exhibition environment and undertaking the unseen work of the museum, to be heard. All the content was translated and recorded in English, Chinese, and Korean and inducted into the virtual museum pages of each language. In other words, the “National Ainu Museum,” with Ainu being the first language and Japanese being the most-used language in its’ physical “form”, has quadrupled as a “virtual image” – Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean- in the online “virtual museum,” and the “quality” of the content has been further enhanced.

Next, we considered the intimacy of “interaction.” Unlike in an actual museum, where many visitors come simultaneously, “visitors” to an online virtual museum often visit alone. In order to successfully convey the significance of the Ainu culture to each visitor, it is better for the researchers and curators who have a comprehensive understanding of the “essence” to speak their minds rather than a professional narrator. For this reason, the virtual museum audio of the National Ainu Museum, including the director’s greeting in Ainu and other languages, is all performed by the museum staff themselves and was recorded and edited by myself in the museum’s sound room. We were able to create an atmosphere as if they were speaking to real-life friends, in a way that was easy to understand for adults and children. As a result, the initial concern that the project might be “too flashy” was no longer a concern.

Finally, I will explain our pursuit to align the virtual museum with the museum’s other online resources. While the items displayed in the National Ainu Museum exhibition rooms represent only a small portion of the museum’s collection, many items are housed in the repository, and their information is accessible via the online collection database which, however, has a low access rate. In fact, four virtual monitors linked to the museum’s collection database exists inside the virtual museum where visitors can easily access a list of the collection.

The Ainu crafts sold at the museum shop were also available through the online store via the web page. A virtual fixture with embedded links was placed in the virtual museum to make these functions easily accessible. Tools for the various resources have been compiled and used effectively.

Future Aspects —— From the Gold Award

As described above, after much trial and error and brainstorming, the National Virtual Ainu Museum was completed just in time for the fiscal year and opened to the public on April 22, 2022.

However, conventionally, the museum’s primary focus has been on the physical exhibits, and both virtual and audio/visual exhibits have been positioned as supplementary and secondary. Virtual exhibits were still not considered as important as the physical ones. Although difficult, my dream is to create a “virtual” exhibition that is interconnected in various ways to online and reality through multimedia and technology and escape the confines of online 3D modeling.

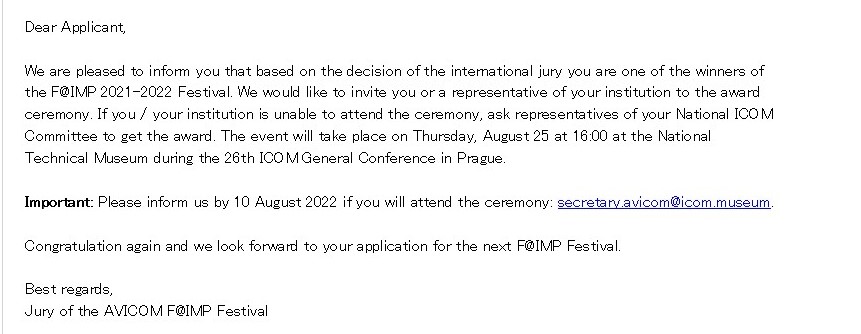

With various sentiments in mind, such as how museums in other countries create exhibitions, how they balance between “virtual” and “reality,” and our wish to showcase our ingenuity to date, I created the film “National Ainu Museum Virtual Tour” to introduce our virtual museum and submitted it to the AVICOM (International Committee for Audiovisual, New Technologies and Social Media) Media Festival (F@IMP) as a member of ICOM. Simultaneously, I submitted a short documentary of the story of Dr. Shiro Sasaki, director of the Ainu Museum, as a museum professional.

In July, I received an email from AVICOM informing me of the award. It was not disclosed as to which film had won what prize and was not made public until we went to the site of the award ceremony to be held during the 26th ICOM Prague Conference.

The award ceremony was in the order of Bronze, Silver, and Gold, with the announcement of the selected international winners, a screening of a portion of the outstanding work, and the next winner being presented with the award. It was amidst the fatigue of jetlag, waiting until almost the end of the ceremony while containing myself from leaving my seat to use the restroom and doubting myself as to whether I will receive an award at all – when we heard “National Ainu Museum” as the winner of the Gold Prize in the augmented and virtual reality section, which is the most representative of new technologies. The Museum director beside me was stunned, and I felt the same astonishment.

I couldn’t be happier that this “virtual museum” was being seen worldwide! In fact, I believe that “virtual” has crucial significance for ethnographic museum exhibits. Few ethnographic materials such as folk tools and costumes are collected in perfect condition because they were items that people of that ethnic group actually used. For an actual exhibition, they are continuously damaged by the loaning and transporting processes. However, “virtual” exhibits created with new technology do not need to worry about damage to the collection, and it is easier and less labor-intensive to update the content.

Furthermore, unlike exhibits of cultural assets such as paintings and earthenware, ethnographic exhibits do not focus on objects but rather on the people of the ethnic group. We want to convey as much information as possible about the people’s culture, lifestyle, and past and future, including their objects. Linguists, ethnographers, and anthropologists learn the language and culture of the people they study and deepen their understanding through long-term participant observation inside the community.

In comparison, it is difficult for museum visitors to gain an overview of an ethnic group’s culture during a short visit. That’s why, rather than a single physical exhibit, utilizing VR and CG technologies to experience a virtual ethnographic fieldwork would have a better effect. More so than a tangible object, the “virtual” holds more possibilities because of its software and flexibility.

Just as cultural properties are divided into tangible and intangible, but equally valued, ethnographic exhibitions must also emphasize the “tangible” and “intangible.” In order to disseminate ethnic culture, a diverse range of activities are expected from merging the two.

(Gaoli Liu)

[i] Weblio https://ejje.weblio.jp/content/virtual

[ii] Eijiro https://eow.alc.co.jp/search?q=virtual

[iii] The Virtual Reality Society of Japan(2011)「Virtual Reality」、pp5-7