October 27, 2022

“Contemporary Art Center” – Giving Shape to Ideas, Creating Intangible Experiences and Memories

[2022.10.27]

Oko Goto

Curator, Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito

What is the Contemporary Art Center?

The Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito, was established as the art department of Art Tower Mito, a cultural complex that opened in 1990. During the 1980s and 1990s, the surge in building art museums was marked by criticism that these museums were “empty buildings without content,” whereas Art Tower Mito gathered attention for appointing artistic directors for the music, theater, and art departments. Art Tower Mito was also recognized for having its own orchestra in the concert hall and a dramatic troupe in the theatre. However, it’s art department’s policy of being a facility without a collection, focusing on special exhibitions rather than permanent exhibitions, and not primarily on collecting and holding artworks, was met with both anticipation and skepticism – as indicated in an art magazine at the time.1

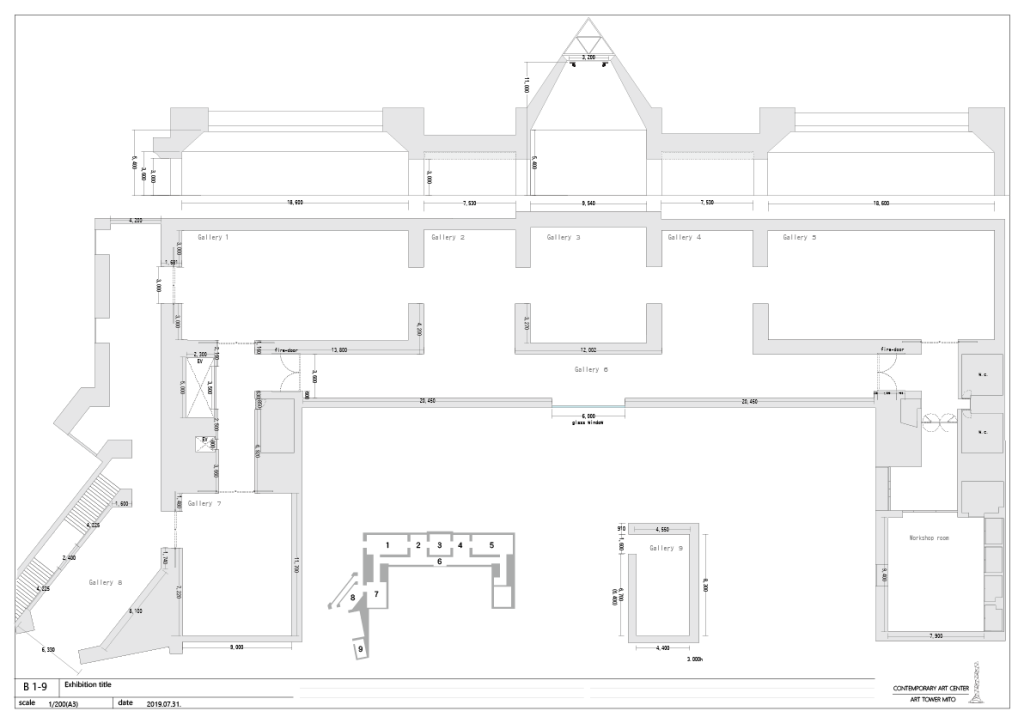

First, allow me to introduce what the “Contemporary Art Center” manages by using the exhibition rooms as a starting point. The Center’s exhibition rooms consist of nine large and small galleries. There are no built-in movable walls or display cases, so temporary walls are assembled to achieve a different impression for each exhibition. The exhibition rooms with 5.4-meter-high ceilings and skylights (Rooms 1 and 5), the rooms with 3.0-meter-high ceilings (Rooms 2 and 4), and the room with the pyramid skylights (Room 3) are connected from west to east, with the corridor-like Room 6 to the south of them. Rooms 2 and 4 have openings on the side facing Room 6, so when they are closed off with temporary walls, each exhibition room can become independent and linear; when opened, the rooms can be interconnected with a multi-directional and meandering flow. Room 7 is a plain cubic space with a ceiling height of 4.2 meters, while contrastingly, Rooms 8 and 9 are directly connected to the entrance hall where the pipe organ is permanently installed. Since the ambiance differs from the rest of the rooms, these rooms are mainly used to showcase works and materials of different natures or for exhibitions that focus on new works by young emerging artists called “Criterium.”

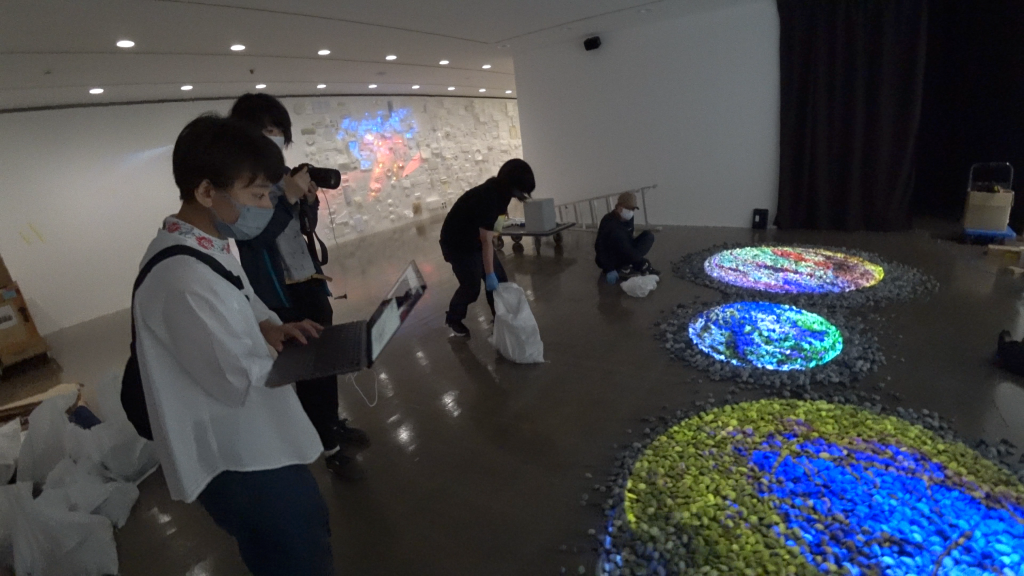

The exhibition rooms can be lighted by opening and closing the shading screens and temporary walls, which allows the rooms to be connected or disconnected from the outside environment, depending on the content of each exhibition. The free reign of cost, temperature, and humidity control are not necessarily beneficial. Still, the highly flexible design adheres to the Center’s concept of prioritizing “temporary exhibitions rather than permanent exhibitions” and therefore embodies the nature of the Center as an intermediate point rather than an endpoint of the collection or a studio. Especially when an artist and curator supervise collaboratively for a solo exhibition, the curator must manipulate the restrictions set forth to materialize the artist’s ideas as much as possible throughout the exhibition. There is also tremendous support from the Center’s Installation Chief, who have been with the Center for more than a quarter of a century, cooperating with the installation staff who have overcome many seemingly impossible hurdles for each installation process.

To cite specific examples from past exhibitions, “Rolywholyover A Circus by John Cage” in 1994 featured live chickens and a violinist performing together in the exhibition room, and in “Daniel Buren/Transparence de la lumière,” a labyrinth of mirrors and stripes appeared in the exhibition room. In “X-COLOR/Graffiti in Japan” (2005), graffiti writers from around the country showcased their skills as the smell of spray paint permeated the exhibition room. The “Resistance of Fog Fujiko Nakaya” exhibition in 2018, in which fog sculptures appeared inside the exhibition room and in the plaza, was well received by both children and adults. After arriving at the Center in 2017, I searched through numerous materials in the Center and tongue-in-cheek anecdotes from senior staff members to conclude about the Center’s “domain,” which is not the pursuit of a specific goal but rather the presentation to the world of expressions that have not yet been defined or evaluated.

Along with planning exhibitions, the Center has also focused on enhancing its educational programs. Since its opening, the Center has conducted artist-led and art appreciation workshops for elementary school students, particularly after recruiting art education volunteers in 1992. The Center began a multifaceted effort to create an “interactive space with citizens.” Recruiting diversified members to “appreciate multiple viewpoints” has always been prioritized and emblematic of the Center’s mission, as it is the norm today; however, it was a bold and unusual choice at the time. Since its precedent as a citizen’s volunteer project in the 1990s, project volunteers activities, where citizens became directly involved in exhibitions and producing artworks, have continued to increase since 2002. Viewing programs for diverse generations and communities were also launched, such as “Gallery Tour for Parents with Babies” (since 2005), “Session! Gallery Tour with the Visually Impaired” (since 2010), and the “Art Bus” program for elementary and junior high school students in Mito City (2008-2019).

Around the same time, “High School Students’ weeks,” which had been held as a free admission month for high school students, evolved into a student-led project, involving local artists and adults, and giving birth to club activities and associations of all shapes and sizes. The relationship between the people and exhibitions is summarized by the words of the Center’s Education Program Coordinator: “Expressions that stir emotions are not always gentle in nature, but receiving and sharing the artists’ works, words, and sincere way of perceiving things has slowly accumulated as an asset to the individual and the community.”2

The Invisible – Virus/ Trust/ Infrastructure

As the world hits the two-and-a-half-year mark since the pandemic started, tensions have begun to fall at a rapid pace. As I look back while writing this article, I wonder if it is possible to conclude anything at this point about the impact of the pandemic, either physically or culturally, positively or retrospectively. I believe that we cannot reach a conclusion at this moment in time yet. For this reason, the following is not intended to be a summary of our achievements but rather a fragment of our efforts at the Center.

The exhibition “Pipilotti Rist: Your Eye Is My Island” (August 7- October 17, 2020, although closed from opening to September 19) held during the fifth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan and under the third declaration of a state of emergency, was a large-scale solo exhibition of Swiss-based, international artist Pipilotti Rist, held in collaboration with the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (MoMAK’s exhibition open from April 6 to June 20). Known for her video installations that transform space without restraint, the composition of Rist’s exhibition focused on the relationship between the viewer’s body and the artwork. Although it would have been preferable for the artist to be present during the exhibition’s final preparations, the artist was absent in Kyoto and Mito due to travel restrictions.

The exhibition was prepared via video conference, with careful instructions from the artist and the technicians, still, much of the detailing was left to the staff’s judgment on-site. Rist’s installations have intended to break free from a stereotypical video format; thus, a “straightforward” exhibition would be insubstantial, and it would require intricate fine-tuning. In addition, a video conference cannot accurately convey factors such as the volume of the work and the overall lighting and color temperature of the space. “Pleasure” and “communal gathering” were the terms used to describe the artworks and experience, and I felt the weight of my role as curator to “welcome” the visitors to the Center as a host of this exhibition. I would be lying if I said I was not anxious. Amidst the uncertainty of the spread of the infection – and under the strain of the state of emergency, how could we create an environment in the place that people can enjoy the “‘glory of life’ where ‘worry will vanish'”?3 There was no other option but to do everything in our power to prepare for the opening, including calculating the number of visitors, applying antivirals to props that numerous people will touch, such as sofas, carpets, and beds, and implementing admission restrictions via advance reservation.

The temporary closure finally ended, and the exhibition was open for a short 26 days. People of all ages were enjoying the artworks – parents and children were casually walking around the venue, people were gazing at the artworks in a daze or falling asleep on the sofa, and elementary school students were lying on the floor peering at a small monitor embedded into the floor- only then I was able to breathe a sigh of relief and wondered if we had been able to live up to the intangible trust placed in us by the artist.

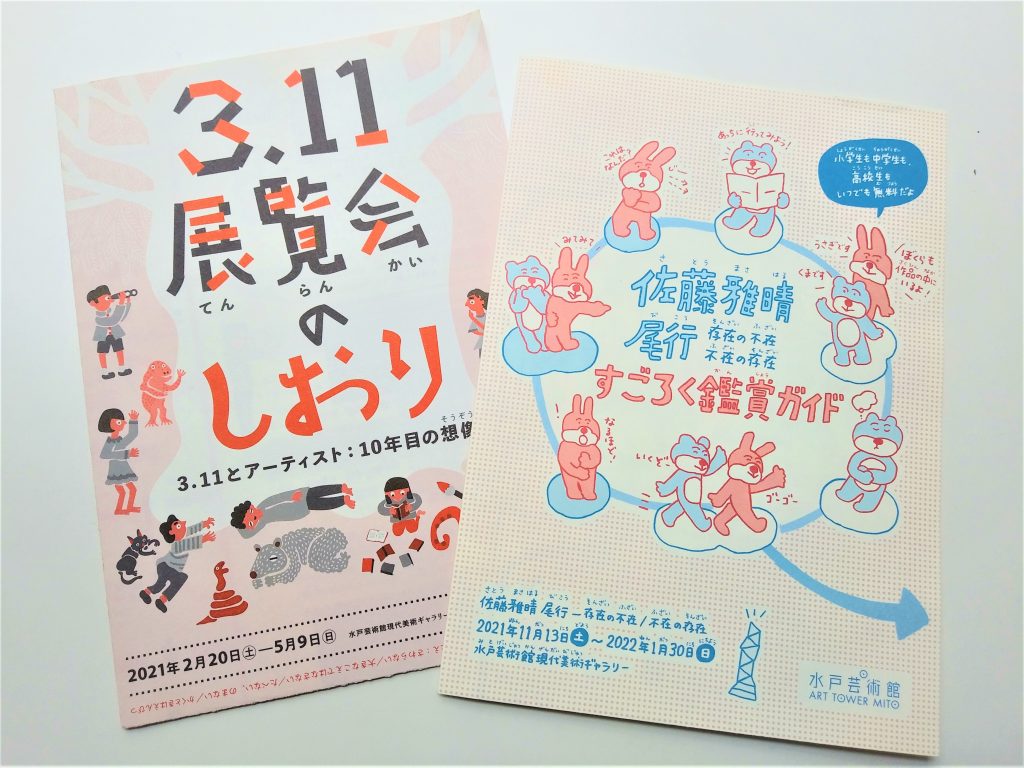

Among the educational programs held throughout the year, the interactive viewing programs were canceled due to droplet-borne and contact infection and replaced by various alternative programs. These programs took various forms depending on the situation, for example, a bulletin board set up in Exhibition Room 8 where visitors could leave comments on post-its, and also a “Dialogue Phone” where visitors could share their impressions of the artworks with “CAC Gallery Talkers (citizen volunteers)” over the vintage telephone (“Michikusa: Walks with the Unknown” and “Artists and the Disaster”); “The Michikusa Exhibition and Scent Archive” (“Michikusa Exhibition”) where aromatherapist Fumio Wada served as a navigator to express memories of the artworks through various scents; and “Usakuma Fortune-Telling,” (Sato Masaharu Trace – Absence of Presence/ Presence of Absence) a sugoroku-like exhibition guide and capsule fortune-telling game written and composed by experienced “Art Bus” guide staffs and the artist, Gojinmaru Hayashi.

At the aforementioned Pipilotti Rist exhibition, a CAC Gallery Talker navigated a post-viewing exhibition tour through the “Living Room After Six,” a relaxing and enjoyable viewing experience in the hours after the gallery had closed. The variations of these interactive viewing programs resulted from reconsidering already proposed plans and also alternate ideas giving birth to new possibilities. In any respect, they were made possible with the unwavering patience of the citizen volunteers who stayed optimistic despite uncertain circumstances.

As a cultural complex, in addition to the programs mentioned above, the Center also provided visitors access to the programs from their homes, such as online distribution of performances held at the concert hall and theater*4 and sales of the “Ouchi-Korabo-Rabo Artist Kit (Home Collaboration Artist Kit)” supervised by artists through an online store. I should also mention that these efforts, whether offline or online, were not only owing to the curator’s planning, and they would not have been possible without the knowledge and cooperation of the staff operating the facility and various platforms and the visitor relations team.

Unhurriedly and Gradually

I had written in the introduction that the Center is “an exhibition facility without a collection,” but this is technically incorrect. In fact, the Center preserves and manages 83 contemporary artworks that have been collected in succession since the days of the pre-opening office. These works were collected “gradually” and “unhurriedly”4 and have mainly been of artists associated with the Center. Works include Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Umbrellas, Joint Project for Japan and the USA (1987) which is part of an art project that will be remembered by the Center and the community at large, and Yutaka Sone’s Her 19th Foot (1993) which was created as a tool for a workshop. The number of works in our collection is modest but diverse in terms of technique and materials.

Among the people who visit not only the Center but art museums in general, a single work of art may open up a new world or be a cherished memory of a visit with someone special. As a public place, a cultural institution differs from a rapidly fluctuating market or art history; it is where multiple time frames intersect. Coincidentally, ATM celebrated its 30th anniversary in March 2020, when the pandemic began. For “Your Memories of Art Tower Mito,” we received many episodes from the public that reminded us of the plurality of time that flows throughout the museum. These personal ties to the arts are another essential resource the Center handles. Creating special exhibitions that must be handed over to the next production after its run and how to preserve the discursive process and experience for future generations will be an oncoming challenge after 30 years, more so than ever.

“Art looks toward the future from the present and has an aspect of foreseeing, predicting, or foretelling what we will be able to create in the future and what our lives and society will be like. In this museum, art will probably await its turn.”5 These words by our founding director are also a mission entrusted to us. In light of Clare Bishop’s definition of “modernity, “6 which has been interpreted from the efforts of modern and contemporary art museums since the late 2000s, the mission of the founding director is no longer a question of separating “permanent exhibitions” from “special exhibitions.” Therefore, the Center will be a place where “contemporary art” creates intangible experiences and memories and gives form to ideas that have no form without being distracted by a “preoccupation with the present” or with “branding.”

- “A New Style of Operation – Mito Art Tower Opens “Geijutu Shincho” May Issue, 1990 p. 74-76

- Junko Moriyama “Trust and Mutual Aid – Reflections on Collaboration with Citizens” ‘Opening the Art Center Phase I and Phase II Record Collection,’ Mito Art Tower, 2019, p.41

- Calvin Tomkins “The Colorful Worlds of Pipilotti Rist” “Pipilotti Rist: Your Eye Is My Island” Exhibition catalogue, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 2021 p.21

- A document from the pre-opening office states, “We are not in a hurry to build a large collection but will collect works little by little.”

- Address by the first director of Art Tower Mito, Hidekazu Yoshida, at the opening ceremony of Art Tower Mito “Art Tower Mito” 1999

- Claire Bishop, “Radical Museology: Or What’s Contemporary in Museums of Contemporary Art?,” translated by Daisuke Murata, Getsuyosha Limited, 2020