June 22, 2021

Time Without Theater: Archiving Canceled or Postponed Performances Under the Pandemic

Ryuki Goto

Assistant Professor,

Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, Waseda University

Introduction

On February 26, 2020, the Japanese government announced a policy of asking people to refrain from hosting “nationwide sporting and cultural events that attract a lot of people” as a measure for preventing large-scale infection risk from the novel coronavirus. Many events and on-stage performances were forced to take the tough decision to cancel or postpone. Initially a two-week deadline was set, but the situation failed to improve and the request to refrain from hosting events was extended from March onwards. In addition to those events that were cancelled or postponed, we should also remember that many events continued to perform with the safest measures in place that could be devised at that time.

On April 7, a state of emergency was declared under the Act on Special Measures for Pandemic Influenza and New Infectious Diseases Preparedness and Response. Cancellation or postponement became the precondition for all performances, and the functioning of cultural industries was suspended for several months. It became a truly unprecedented situation, the like of which could not be found even when looking back through history. According to a survey by the Development Bank of Japan, 12,705 live music or live performance events were cancelled or postponed from March through to May, with an economic loss estimated at 904.8 billion yen[1]. The performing arts industry faced an economic crisis, and demands for compensation were made throughout Japan. Theater companies, theaters and related groups formed an unprecedented broad coalition. For example, the Japan Performing Arts Solidarity Network[2] was formed, with mediator roles taken up by Hideki Noda (of NODA MAP), Atsuo Ikeda (Managing Director, Toho Co., Ltd.), and Chiyoki Yoshida (President of the SHIKI THEATRE COMPANY). The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University (“Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum”) was the only academic society to list its name among the network’s sponsor organizations.

On May 25, the emergency declaration was lifted nationally, including in Tokyo Metropolitan Area, and preparations were made to restart activities in each field. In the performing arts industry, many theaters relaunched performances, with careful measures in place in accordance with the guidelines, and ongoing efforts were made on a trial-and-error basis. However, as I write on September 9, the situation still leaves no room for complacency[3].

In catastrophic times such as these, people often refer to similar incidents from the past. Possible examples of the relationship between historical pandemics and theater include the spread of cholera in the late Edo and Meiji period[4], and the global spread of Spanish Influenza[5] around 100 years ago. However, I was unable to find any compilations of records from these eras. This is perhaps another reason why we need to leave a record of the current situation, when performances are being cancelled and postponed as a result of the pandemic.

Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum is a research institution for live performance and video culture, as well as a museum. In view of the above situation, since April we have been investigating and collecting materials related to the public performances that were forced to cancel or postpone to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Our aim is to establish a record from the perspective of theater today, as impacted by the pandemic. In this way, we will leave records and memories of the performances that could not be shared in 2020 for future generations.

In this column, I will report on the measures implemented at Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum amid the ongoing spread of COVID-19. Please note that the investigation and materials collection focuses on live performance (performing arts). I have not covered video (film and TV, etc.), which is another pillar of research at the museum.

1. COVID-19 measures implemented at the theater museum

Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum is the only theater museum in Asia, and one of few worldwide. It opened in October 1928 to commemorate the 70th birthday of Professor Tsubouchi Shoyo and the completion by him of the translation into Japanese of all 40 volumes of the “Complete Works of Shakespeare.” Leading figures from all areas of society, such as Eiichi Shibusawa, helped to promote the museum’s opening. In a speech given at the museum’s opening ceremony, Tsubouchi described his hope that the museum would become a place where comparative research could be carried out into plays from around the world, both old and new, and that it would help to bring together materials and literature under a single roof for the purposes of contrast and examination. He also set out the purpose of establishing the museum by explaining that in order to produce the best theatrical performances it is necessary to build a foundation by collecting play-related materials from both Japan and overseas, old and new, organizing them, and carrying out comparative research[6].

Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum collects and stores a diverse range of drama-related materials from all ages and countries, in keeping with the original wishes of our founder. These include books, magazines, scripts, manuscripts, diaries, letters and nishiki-e prints, as well as photographs, film, video, audio sources, clothing, large and small props, playbills, synopses, fliers, posters, programs and tickets. There is an incredibly wide range of materials, totaling around one million items. We have given something back to society by sharing these items widely and making them available for viewing or exhibitions.

We have tried to respond to the question of how to hold on to a “theatrical performance”, which does not retain a tangible “physical” form. Theater is made up of numerous different elements and for this reason our “materials” take on the wide variety of forms described above. While a play itself does not remain, by collecting a wide range of related materials we have tried to bring to life the core elements of each play that are left in the vacuum. For example, the items that are consumed for each performance, such as fliers, posters and tickets, offer proof to us that a play was performed (expressed) in that time and place…that the play truly existed.

Expressions of a temporary nature, which includes all performing arts and not just plays, do not actually become works of art unless they are actually performed at the time. The cancellations and postponements brought about by COVID-19 have stolen these works from us. However, rather than treating the time dedicated to these performances as though it never happened, our hope is to leave records and memories of the thoughts and feelings of those involved in each performance. This includes those involved in production, such as the writers, directors, actors and staff, as well as the audience members who should have been taking their seats in the theater that day. Under the impact of the pandemic, materials such as fliers and posters take on a more profound meaning as proof that these performances existed (or should have existed).

As explained above, the roots of this project lie in our museum’s approach to investigating and collecting materials, which has guided us since we opened. We see this as an extension of our normal everyday activities in the sense of creating an archive of performing arts materials. However, in the history of our museum, which goes back more than 90 years, this is the first time we have attempted to focus our efforts at collecting materials in a way that responds immediately to a situation that society is faced with. In the next section, let’s go into a more detail about the processes behind this work.

2. Investigating the cancellation and postponement of performances

On April 6, I received a letter from Waseda University Administration Offices stating that entry into the campus was prohibited and that I was to work from home (initially from April 8 to 21, but this was later extended on several occasions in response to the ongoing situation). When the state of emergency was declared, I was in the middle of sorting through my work and making preparations to work from home. With the closure of the campus, all of the projects that museum staff had been carrying out were suspended.

In terms of the impact on exhibitions, an exhibition of a new collection (April 6 to 22) was cancelled. Our spring exhibition “Inside/Out: LGBTQ+ Representation in Film and Television” (May 16 to August 2), our special exhibition “The Heroes from Romance of the Three Kingdoms: Fantastic Stages in Japan, China and Taiwan”[7] (as above), and our permanent exhibitions were all postponed to the autumn[8]. As a result, the autumn exhibition and special exhibition were postponed to the next academic year. The museum is located on the university grounds, so we needed to rack our brains to come up with ways of working from home amid the campus closure. This was the first thing we needed to think about.

In response to a request made in late February 2020 to refrain from holding performances, we saw a large number of theaters decide to cancel or postpone performances through to early April. It would be reasonable to assume that the situation became even more serious after the declaration of a state of emergency. This was when the museum started to investigate the cancellations and postponements of theater performances caused by the growing spread of COVID-19. The project was led by our staff who are responsible for handling modern Japanese theater. We used the Internet (including the official websites of performing groups and related organizations, as well as SNS and news websites, etc.), newspapers and magazines to collect and organize information about the cancellations and postponements of performances, and the related discourse. Furthermore, because of the global scale of the crisis, we asked for help from our staff responsible for both Western and Eastern theater and collected information from overseas. Eventually, this would be developed into a museum-wide project carried out by all of our staff.[9]

Carrying out this task with a small team while working from home was extremely difficult, but we collected as much information as we could. We created lists of cancelled and postponed performances, as well as chronologies that made it possible to cross-reference COVID-19 infections against wider trends in theater and culture (this work is ongoing).

3. Asking for performance-related materials and the response

After the state of emergency was lifted, Waseda University sent a notification to ease restrictions on entering the campus from June 1. In June, we commuted to the campus whenever it was strictly necessary to do so, while continuing to work from home as a general rule. From June 29, we adjusted our attendance to around 50% on-campus attendance, and switched to a mixed attendance system that combined working from home with coming into campus.

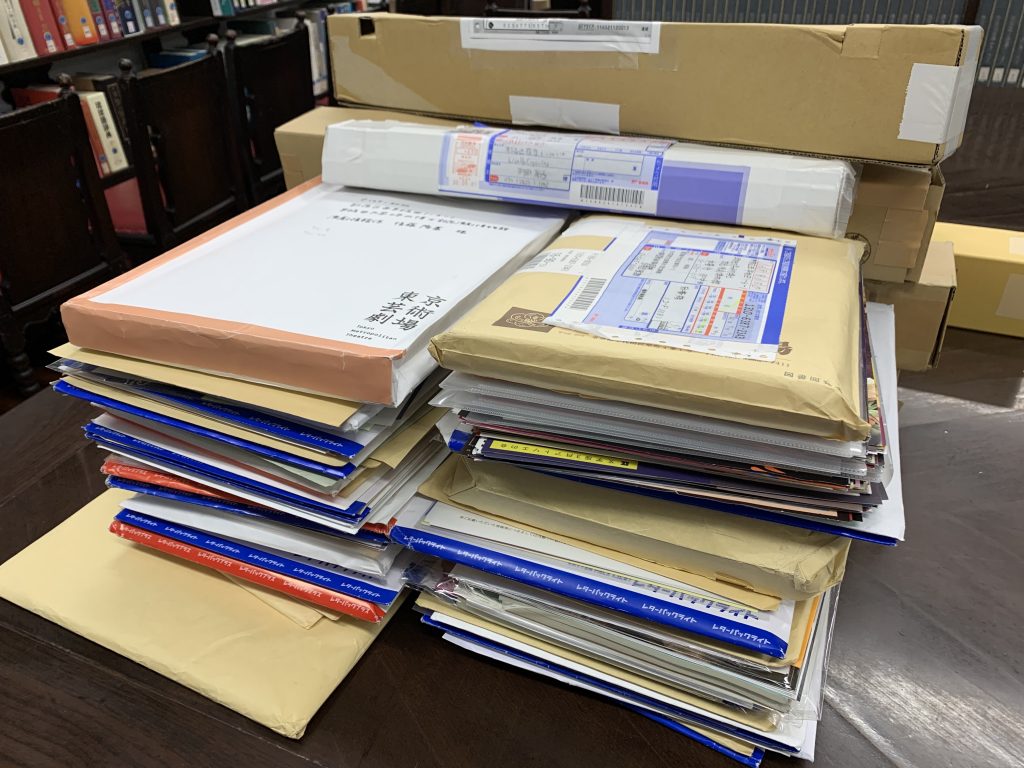

In normal times, our museum receives vast numbers of fliers (or posters) containing notices and advertisements of performances, which we have accumulated. Bundles of fliers that are handed out on entry to theaters or placed on seats can become valuable theater materials. Before the campus closure, we received approximately 250 different fliers dating to before the decision to cancel or postpose because of COVID-19. After we were able to return to the campus, in addition to our regular work, we set about gradually sorting through these fliers and cross-referencing them against the lists of cancelled and postponed performances.

As this work progressed, we were aware that we did not have materials for every performance that had been cancelled or postponed, which was to be expected. This was why we made a large appeal for theater materials, with the aim of archiving as comprehensive a survey and collection as possible. Collecting materials that tell the story of the time of COVID-19 is something that other museums have already been doing, but our project was to do this through the lens of theater.

On June 18, an appeal was launched on the museum website and SNS, targeting performing groups, theaters, and related organizations[10]. We decided to include the following among the donated items:

(1) fliers (in cases when no prints were available or when the performances had been cancelled or postponed before these had been printed, we asked them to provide us with the digital format)

(2) posters

(3) programs and pamphlets

(4) props

(5) direct mail correspondence notifying the cancellation of performances, etc.

(6) any other items that represented performances, including ballet, opera, dance, etc. (in fact, we made no distinctions by genre, and accepted everything that was sent to us)

We had heard rumors that preparations were being made to dispose of advertising materials for performances that had already been cancelled or postponed. Taking into account the fact that many of the groups would not be able to send these to us right away, we added a request to store the items for the time being without disposing of them.

After launching the appeal on the website and social media, we were lucky enough to be featured in the online Bijutsu Techo magazine. Our museum’s Twitter posts were widely shared and the word spread. We gave interviews to various media, and around one month after our initial appeal we had received the cooperation of around 40 organizations. At the same time, we have also made individual requests to each group. We are incredibly grateful to have received affirmation and support for our museum’s project from so many groups, despite the tough time they were having. In addition, we reconfirmed the strong level of expectation and trust that our museum has received from the theater industry and its supporters. As a member of Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, I am keenly aware of the need to treat this trust with the respect it deserves.

The people who have shared materials with us have one thing in common – they have all expressed sympathy with a project that aims to collect and make available as a public “record” the situation faced by the cancellation and postponement of performances which they can now only retain in their “memories.” As well as the heart-wrenching decisions to cancel or postpone and the struggles they had gone to in creating their pieces, we also heard about their confusion and struggles amid the constantly changing situation as they prepared performances that might never be made public and created fliers that might never be used. On top of this, they made preparations to reopen with a view to the future.

As of September 9, we had collected more than 400 performance materials from approximately 150 performances[11] and around 80 groups, covering a diverse range of genres, from traditional performing arts through to modern theater. We collected materials regardless of size or region and included everything from fliers, posters, props, direct mail correspondence and website notices of the cancellation or postponement of performances, as well as video clips. This also included materials related to the performance of plays for children and young people, which tend to get less publicity than plays for adults.

In academic year 2019, Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum hosted an exhibition “For Our Children’s Tomorrow: Contemporary Japanese Theatre and Young People” (November 2 to December 25) and a special exhibition “How crazy, Japanese Puppet Theatre!” (November 2 to December 24). These exhibitions offered broad coverage of the history of young people’s drama in Japan, in a way that was accessible to people today. We need to continue this work, which goes back to the research and practice of children’s drama carried out by Tsubouchi Shoyo himself, and to the history of projects carried out at our museum. To remain sustainable as a museum, we have to make sure that our work, including our current project, possesses continuity with an awareness of the future[12].

4. Opening up and communicating the collected materials to the public

How will we make use of the collection of theater materials we have collected? Our first aim is to store and organize a collection of theater materials that tell the story of the time of COVID-19, and to create an environment that allows as many people as possible to access it.

We have also planned an exhibition on the relationship between the pandemic and theater. Firstly, on October 7, around half a year on from the declaration of a state of emergency, we planed to hold an online exhibition using fliers for cancelled or postponed performances called “The Lost Performances – Records and Memories of COVID-19 and Theatre”[13]. We chose to carry out the exhibition online as a way of responding to the times and to prioritize the importance of holding an exhibition in the midst of the crisis, with a view to the future potential for a digital archive.

The purpose of the exhibition is essentially the same as the goals behind collecting materials that I described earlier. Rather than seeing an empty space as an empty space, we will record the very fact that these performances were not put on. This is our chance to pick up on the thoughts and voices of the people forced to face up directly to the cancellation and postponements of performances, including the audience and the creators, and to make these voices audible to others. I sincerely hope this will encourage our theater staff who continue to struggle greatly.

Another objectives is to cast a spotlight on “fliers” as “works of arts.” In addition to the fliers (listing credits for promotional artwork, etc.) and details of the performances, we want to pass on individual memories and thoughts by recording the comments of people involved with the performances. At the same time, we will provide multi-layered perspectives through messages on the relationship between the pandemic and the performing arts, as well as culture in a broader sense. We plan to continue updating the exhibition on a regular basis in response to the changing situation. For example by continuing to make individual requests for the provision of materials, organizing materials, and receiving comments. Our project will not end with the release of the online exhibition. Instead, it should perhaps be described as a new start.

We plan to use the online exhibition as a platform for a physical exhibition of materials (planned for Academic Year 2021), using categories of materials other than fliers. In order to achieve this, as well as the “lost performances,” we also need to pay attention to the performances that were “not lost” and were actually put on during the pandemic. Doing this is certain to provide us with more angles from which to consider the relationship between COVID-19 and theater.

Conclusion

The performing arts world has suffered devastating damage from the pandemic. Theater itself was not lost. But we cannot deny that theater has lost time. Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre’s project aims to cast light on this “time.”

Events that truly occurred are recorded and eventually become part of history. However, events that didn’t occur (even if they had the potential to do so) might remain in people’s memories but become erased from the historical record and forgotten. We will leave a record of such events, and turn them into history. We will create an archive of the records of “lost performances” as individuals remember them and communicate this to the world. This very act will become part of history, alongside the ongoing impact of the pandemic in the “here and now” (although we may already be starting to lose the period of time from late February 2020 as it becomes the “past.”)

Looking ahead, it seems likely that we will be forced into changes and a rethink, not only when it comes to creating performance pieces but also in terms of the systems and spaces for theater (entertainment). As it becomes more difficult to maintain the old theater environment because of restrictions on audience numbers and infection prevention measures, etc., what is the best way of responding to this disaster? Some performances have been put on after seeking new methods, and attempts have been made at distributing video content and carrying out online performances, etc. Even if these do not become the mainstay in the immediate future, it would be encouraging to see them as early signs of potential new forms of expression and communication, rather than just as temporary alternatives. These methods would be useful ways of providing content to faraway locations, irrespective of distance, and they pose questions that shake the concept of theater, built as it is on the assumption of live performance.

Meanwhile, as theater-related media increasingly move online, how many of the current “materials,” for example paper media such as fliers, will remain? When running an organization, the decision about whether or not to print advertising materials, which is a major expense, when you cannot be certain whether or not the performance will go ahead, is likely to be an urgent question that cannot be overlooked. Even as the pandemic comes to an end, there is still significant scope for change.

If theater is advertised or performed online without the printing and distribution of fliers and posters, there may be an increase in performances that, in addition to leaving no record of their expression, also leave none of the tangible paper “materials” that our museum has collected until now. Changes in the systems for theater (entertainment) will have a huge impact on how our museum works, including the nature of materials themselves and how we collect them. What forms of theater will remain in a post-COVID-19 world? We will need to keep a close eye on overall trends in the world of performing arts.

(Ryuki Goto)

[1] https://www.dbj.jp/upload/investigate/docs/150bfb2cdd75287200bd7abd2f73b312.pdf (last viewed: September 1, 2020)

[2] https://www.jpasn.net (last viewed: September 1, 2020)

[3] For further information on conditions in the theater industry and related fields from February onwards, please refer to the following studies by Ryuichi Kodama, who put together a record of the trends in real time: KODAMA Ryuichi, “二・三月 劇界の動向” (Theatre Trends from February to March)“演劇界”, May 2020; “三~五月 劇界の動向” (Theatre Trends from March to May) “演劇界”, June/July 2020; “五~七月 劇界の動向” (Theatre Trends from May to July) “演劇界”, August/September 2020; “七~八月 劇界の動向” (Theatre Trends from July to August) “演劇界”, October 2020; “八~九月 劇界の動向” (Theatre Trends from August to September) “演劇界”, November 2020.

[4] Please refer to HIOKI Takayuki, “安政5年(1858)コレラ流行下の中村座” (The Nakamura-za Theatre during the Cholera Epidemic of 1858) https://researchmap.jp/blogs/blog_entries/view/95331/884d6f768f6babd9d5f82d99ff bbcdf9?frame_ id=530861 (last viewed: September 1, 2020), SASAYAMA Keisuke, “新型コロナ‘興行大打撃’は,コレラ流行の時代と驚くほど似ていた” (Startling Similarities between the Damage to Entertainment from COVID-19 and the Time of the Cholera Epidemic) https://gendai.ismedia.jp/ articles/-/71311 (last viewed: September 1, 2020)

[5] Please refer to GOTO Ryuki, “スペインかぜの記録” (A Record of the Spanish Influenza), Tokyojin Issue 432, December 2020 issue (planned)

[6] Edited and published by Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, Waseda University, “演劇博物館五十年” (50 Years as a Theatre Museum), 1978, pp.126-127.

[7] The initial plan was to host a special exhibition called “Classical Chinese Opera in Taiwan” (provisional title). However, GuoGuang Opera Company from Taiwan, with which we had been in touch, was affected by COVID-19 and it was decided to cancel on March 19. “The Heroes from Romance of the Three Kingdoms: Fantastic Stages in Japan, China and Taiwan” was rapidly put together as an alternative exhibition.

[8] On September 10, Waseda University Administration Offices decided to reopen the museum from September 28.

[9] As part of the special themes research established by the Collaborative Research Center for Theatre and Film Arts in Academic Year 2020, we carried out “Investigative Research on the Japanese Theatre Industry under the Impact of Novel Coronavirus Infections” (Research Representative, GOTO Ryuki). As part of this research, we have also carried out the following “Performing Arts and Cultural Policy under COVID-19: A Case Study from the West” (Research Representative, ITO Masaru), and “Survey of Measures to Prevent Novel Coronavirus Infections in Museums, Art Galleries, and Libraries” (Research Representatives, SATO Yuki and KURI Nozomi). The latter of these projects was released by the Collaborative Research Center for Theatre and Film Arts under “Survey Report on Measures to Prevent Novel Coronavirus Infections at Museums, Art Galleries and Libraries” (http://www.waseda.jp/prj-kyodo-enpaku/research/file/report_covid-19_20200619.pdf)

[10] http://www.waseda.jp/enpaku/covid19_notice_research

[11] When counting the number of performances, Tsubouchi Museum Theatre counts each piece as one “performance,” rather than counting the number of times the performance is staged (performed). However, the number of stagings is often used in surveys by other organizations. For this reason, in future we also plan to calculate the number of “stagings” alongside the number of “performances.”

[12] Please also refer to KUBO Yutaka, “あの虹に届くまで、りんごの木を植えつづける” (I’ll Keep Planting Apple Trees until I Reach the Rainbow) (“Inside/Out: LGBTQ+ Representation in Film and Television” Catalog, The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University, 2020, pp.95-97, edited by KUBO Yutaka)

[13] Online exhibition held on October 7 while this paper was being proofread. (http://www.waseda.jp/prj-ushinawareta)