June 17, 2021

Significance of Collecting Materials Related to the COVID 19 by a Museum

Makoto MOCHIDA

Curator, Urahoro Town Museum;

Researcher, Division of Academic Resources and Specimens, The Hokkaido University Museum

1. Collecting COVID-related materials as an extension of daily collection activities

The Urahoro Town Museum is located in Urahoro Town, Tokachi-gun, which has a population of about 4,500 people and sits right between the Tokachi and Kushiro regions of eastern Hokkaido. The museum appoints one full-time curator for the fiscal year. There is no full-time museum director. It is a typical community museum focused on local materials that does not specialize in any particular time period or field.

Currently, the museum is collecting “COVID-related materials,” which are materials that document how local lifestyles have changed as a result of the recent novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) becoming a society-wide issue. I believe that one of the factors that enabled us to start collecting COVID-related materials as soon as possible was the fact that we are a community museum that does not limit itself to any particular field of study and have a very small-scale organization.

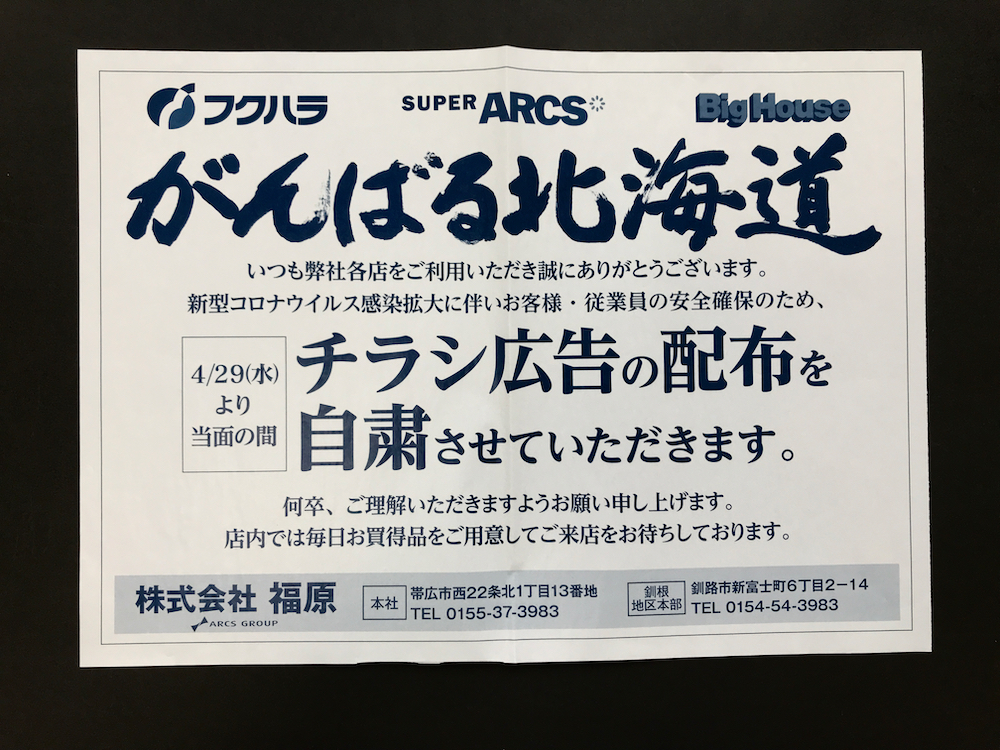

There are two main developments that led to the museum’s collection of COVID-related materials. One is our industrial materials collection. The museum has been collecting newspaper “inserts” for some time. Collecting inserts over time can reveal a wide variety of information, such as 1) changes in the type and number of stores that issue the inserts, 2) changes in the products listed in them, and 3) changes in typeface, color, and other aspects of their design. We have also been collecting various notices issued by civic and other organizations as a form of “daily-life materials.”

Our current collection of COVID-related materials, therefore, is an extension of these daily activities. In particular, from February 2020 when Hokkaido declared its own state of emergency, there was a striking change in the content of the inserts, and eventually the number of inserts themselves decreased dramatically. These changes were one of the reasons why we started making a conscious effort to collect COVID-related materials.

Kido (2020)[1] observes the content of articles in the Futoko Shimbun (a newspaper for children not attending school) over time and attempts to identify new issues related to the problem of school absenteeism in the age of COVID-19. Similarly, research has already begun in various fields on the changes taking place amid the age of COVID-19. What is unique about our museum’s newspaper insert collection, however, is that it documents these changes from before COVID-19.

A museum that collects the “now”

The other main development is a lecture by Naoaki Ishikawa, curator and director of the Otaru Museum, titled: “Museums that Collect the ‘Now’: The Role of the Community Museum in Documentation.” This was held as a lecture at our museum in 2016. Curator Ishikawa’s efforts are also summarized in volume 47, issue 9 of this journal (Ishikawa 2012)[2], which I will refer to here.

In that article, curator Ishikawa mentions the gangan, which formed an essential part of the historical scenery of Otaru City. After WWII, there was a group of people who used 18-liter tin cans and other containers to transport fresh foods, mainly fish, from the port city of Otaru to surrounding coal-producing areas. These people, who lined up in the Japanese National Railways’ peddler-dedicated early-morning train car, were called the gangan butai (the “gangan troops”). They were a typical sight in the port city of Otaru during the postwar period.

Materials about the gangan, however, have not been collected by museums. Curator Ishikawa introduces this as an example of a failure in materials collection. This failure may be due to the fact that the Otaru Museum and other museums at the time were less conscious of the need to collect consumable items such as those carried by the gangan than they were of the need to document refrigerators and other home appliances in use at the time. Ishikawa also mentions that the items subject to collection were selected based on practical aspects, such as a community museum’s physical capacity and budget for collection.

The majority of materials currently being collected by our museum are “ephemera materials,” or transient notices and posters, such as notices of event cancellations and calls for self-restraint. If we do not collect them now, in the midst of the pandemic, they will be discarded as soon as they have served their purpose of notification. Just like the gangan of Otaru, if someone does not point out their “resource potential” and consciously collect them, such objects will not remain. Will this not lead to a complete forgetting of the history itself that is reflected in these objects, that is, the plain, everyday memories of the people who lived through the age of COVID-19?

Therefore, our museum decided to focus on collecting COVID-related materials along with our daily collection of inserts and notices. Collection work is mainly performed by the curator, but administrative staff, temporary staff, and even museum volunteers are also invited to help. We keep a constant eye out for materials to collect.

We have also explained the significance of collecting COVID-related materials and called for donations through the museum’s magazine and social media. Initially, we only planned to collect materials from the vicinity of Urahoro Town. However, our collection gradually expanded in scope, and due to the urgency of this project, we are currently accepting materials without specifying any particular target area. Materials from outside the town’s vicinity will be sorted out to some extent once they have been collected. We are considering transferring them to other facilities after consulting with museums and libraries in each area.

3. Notes on collection and organization

Initially, the curator collected whatever materials he happened to notice himself. Eventually, however, our museum began to openly call for materials, and we arrived at the difficulty of defining what exactly COVID-related materials are in concrete terms. What we are looking for are things such as posters that state, “To prevent the spread of infection, we have stopped serving food and drinks,” or notices that say, “Please refrain from holding funeral ceremonies,” and so on. Very few citizens are aware that such things can be used as museum materials.

Therefore, the museum decided to set up a “sample display” consisting of two glass cases (originally one, but we added another) in the lobby in front of our permanent exhibition room to notify the public that we are looking for these kinds of materials. This is what is being introduced as a “special exhibition” in the press these days, but in fact the real exhibition is scheduled to take place in February 2021 (one year after Hokkaido declared its own state of emergency). The current exhibition is nothing more than a “sample collection.”

Our museum registers its collection materials with four-digit classification numbers. However, this time, we decided to stop classifying COVID-related materials. We instead give them the common number of “6540” followed by a serial number in the order of the date of acceptance (an acceptance number, which serves as the resource number in this museum).

There are two reasons why we stopped classifying these materials. The first is to save the time and effort involved in categorizing each material as “industry” or “education,” for example, and to speed up the registration process.

The other reason is that categorizing materials inappropriately may limit their potential for future use. We are trying not to think about setting any objectives for these materials, such as: what will we use them for in the future? Or: what kind of projects or research will they be used for?

For now, our attitude can be summed up as, let’s just collect and keep whatever we find interesting. We don’t know what field it will be useful for in the future. But if we hold onto it, it may be useful for something.

This is true not only for research, but also for future exhibitions. With the exception of the special exhibition in February next year, these materials are not necessarily intended for display (there is nothing that looks particularly good on display in the first place).

We prepared several storage bins dedicated to “COVID-related materials,” and stored the materials in them in the order they were collected. We started to organize and store some of them in clear file folders, but have not yet progressed very far in the organizing process.

We emphasize record-keeping on resource cards. In other words, recording the secondary information, such as when, where, and by whom was the material collected? Or—who made it? How did we obtain it? This is because the value of a resource is enhanced when it is accompanied by a story such as, “Relatives living in China sent me masks from China when they learned that Japanese masks were in short supply.”

Unfortunately, our museum has not made any progress with digitization. Even now, we fill out all the required items on a thick card called a “Resource Record Form” (original record) by hand and with rubber stamps. Then we print out a photo of the resource using a printer and paste it on the form. Creating this form for each insert entails an enormous amount of labor, and we are working on it with the help of museum volunteers.

4. The response to our COVID-related materials collection

The most common response we have received regarding the sample display in the lobby and through newspaper reports is, “Why bother to keep these things?” The implications of this is that no matter how many times our museum calls for people to donate materials, we will not be able to gather the materials we are looking for through public cooperation alone. Conscious collection by the curator is the key to preserving these materials, after all.

Some people even said, “If anything, I find the idea of deliberately documenting painful history—unpleasant times that we want to forget as soon as possible—to be baffling.” Here, too, I sense that we are already in danger of losing the legacy (records) of life in the age of COVID-19. The attitude of “let’s forget about unpleasant things as soon as possible,” is, in a sense, necessary for social life. However, it is dangerous from the perspective of documenting our daily lives. It is also linked to the danger of our memories not only fading over time, but also of our memories being distorted and beautified. That is why, if we are going to collect these materials, we must do it now, while the pandemic is still with us.

“What do you think they will be useful for?” To this question, recently, I have been frankly answering, “I don’t know.” In fact, I had initially responded to this question by listing possible research topics. However, to the extent possible, I am trying to avoid saying anything about the direction of their utilization. This is to prevent the museum from attaching a fixed “color” to the attributes of these materials.

Some people have also asked, “What is the point of a community museum (or board of education) collecting and preserving things that are not meant to be exhibited?” The only way to answer this question is to persistently and firmly explain the significance of why museums should collect COVID-related materials in the first place.

5. Why collect COVID-related materials?

When we see a picture of a poster that reads, “Luxury is the enemy!” posted on a telephone pole on a street corner, we are able to get a feeling of what the world was like during World War II because there were people who kept records of posters at that time. In the same way, today, museologists and curators who live in the present stand at the forefront of closely observing the age of COVID-19 and collecting objects to document this history.

To leave behind materials that people can look back on five decades or a century down the line and say, “so this is what it was like in those days”—this is the reason why museums preserve and pass down history in the form of objects. Community museums, however, also play the role of documenting the plain, everyday lives of ordinary people, which are left out from the “official” records written down by the national and local governments in official documents and in town histories. The mission of the museum should be to gather and preserve materials that will be useful when we try to look back objectively at what was actually happening at a particular point in time, not just textbook descriptions that are convenient for the authorities.

Unlike tsunamis and earthquakes, infectious diseases do not change the townscape and other everyday aspects of life. The changes are manifested not in the outward appearance of the city, but in the daily lives of the people. Government announcements, rumors in the streets, and the lives of people at the mercy of these rumors have been changing at a dizzying pace in just six months. The characteristics of the time we live in now are revealed in the very speed and content of these changes, and it is our role to figure out how to document them.

What havoc does an unknown infectious disease wreak on our lives in society? The COVID-related materials we are collecting now will undoubtedly be useful for considering social measures in the future when other new, unknown infectious diseases emerge.

6. Challenges and future prospects

Efforts to collect the “now” and document it in history are by no means new. But how should we collect, organize, publish, and utilize these materials? Methods of documentation and the like are still in the process of development.

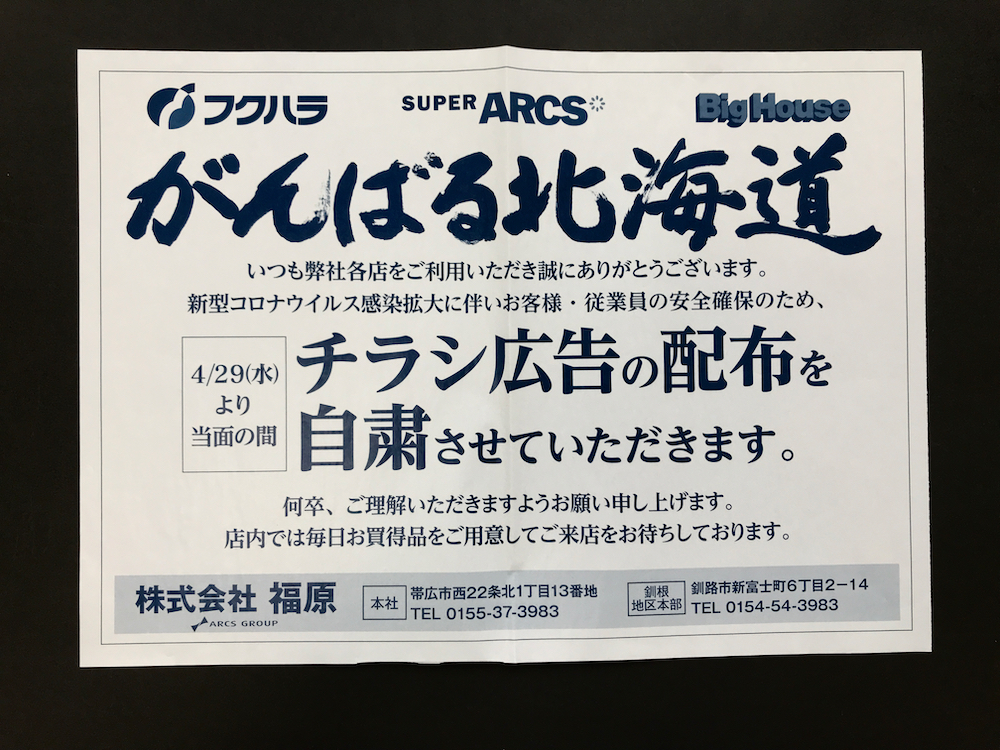

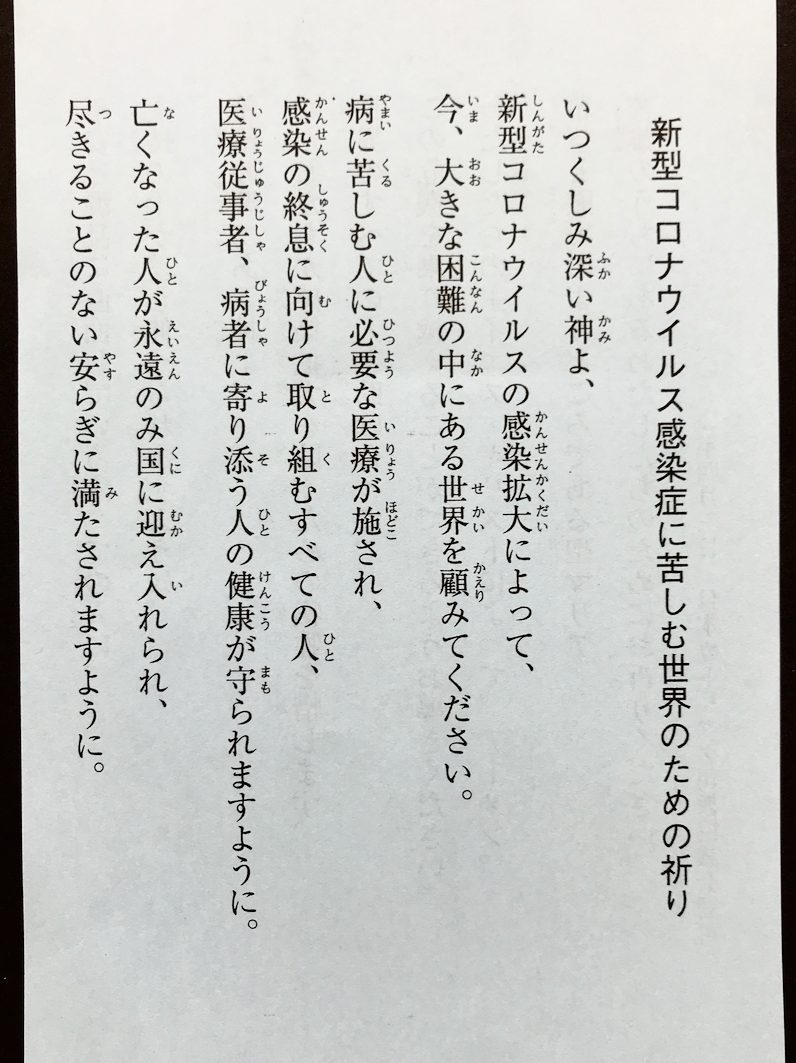

Endo (2019)[3] introduces a case study on collecting the menus of popular restaurants, stating that “the actual situation of what and how the general public eats is rather difficult to grasp.” This also applies to Urahoro Town during the current pandemic. When people were urged to refrain from eating out to contain the spread of the virus, each restaurant devised takeout menus, and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry began issuing coupons and menu lists. These items are being collected as materials.

Yoshiro Sugawara, a curator at the Otaru Museum, is working to take documentation one step further. With the cooperation of a Chinese restaurant, he took photos of the shumai being sold by the restaurant as a takeout-only item due to COVID-19 measures, including photos of its contents and what it looked like in the steamer. Curator Sugawara says, “Today we can easily take photos with our smartphones and other devices, and view photos of food on the Internet whenever we want. Looking back at the museum’s collection of materials, however, I realized that although we had signs, containers, menus, etc., there were surprisingly few photos of the important dishes” (from private correspondence with Mr. Sugawara).

This problem of documenting the history of the culture of everyday life is one that I have become aware of by collecting COVID-related materials. I would like to consider a similar method for our museum in the future.

One thing that the museum has not been able to collect enough of is materials related to children’s studies and daily lives during the period when schools were closed. We have asked some teachers to cooperate with us individually, but there is an atmosphere of fear in school settings that information about the children (especially their names), will remain. As a museum, we believe that objects with names on them and things that can identify individuals are more concrete, and thus have a higher value as resources. On the other hand, it is also true that explaining this is difficult simply because the museum has not yet set a direction for how these materials will be used. We are planning to try to request cooperation in writing through the Board of Education (principals’ association).

Equally difficult to collect are materials related to discrimination and prejudice that have occurred in various places, triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Large-scale epidemics of infectious diseases often create discrimination and prejudice due to misinformation, insecurity, and fear. Regarding this, the Japanese Psychological Association was quick to issue a call for action[4]. In the field of clinical psychology, there is much discussion about the causes of social anxiety and mental health care[5]. However, in reality, collecting such materials has been difficult. This may be partly due to the fact that “there are no objects” to begin with.

People’s thoughts and feelings, which in the past were written in diaries and letters, are nowadays transmitted digitally through emails and social media. Discrimination and prejudice cannot be collected as long as the emphasis is on “collecting objects.” Such examples can only be documented after interviews are conducted and curators put them into print. In the future, new methods of collection will be needed, such as the screensaving of discriminatory words and actions on Twitter. Our museum is not currently working on this. However, it goes without saying that interviews, photographs, and other records made in parallel with the collection of objects will eventually increase the degree by which life at the time can be reproduced when these resources are used in combination with the objects left behind.

Just like how eateries in Urahoro, which did not have a take-out culture, suddenly developed take-out in response to the pandemic, we can expect different phenomena to occur in urban and rural areas during the same COVID-19 era. The scenes seen and atmosphere felt at a prefectural-level museum and at a municipal-level museum will probably be different. The challenge is how to systematize this. However, it is thought that many materials for achieving have already been lost.

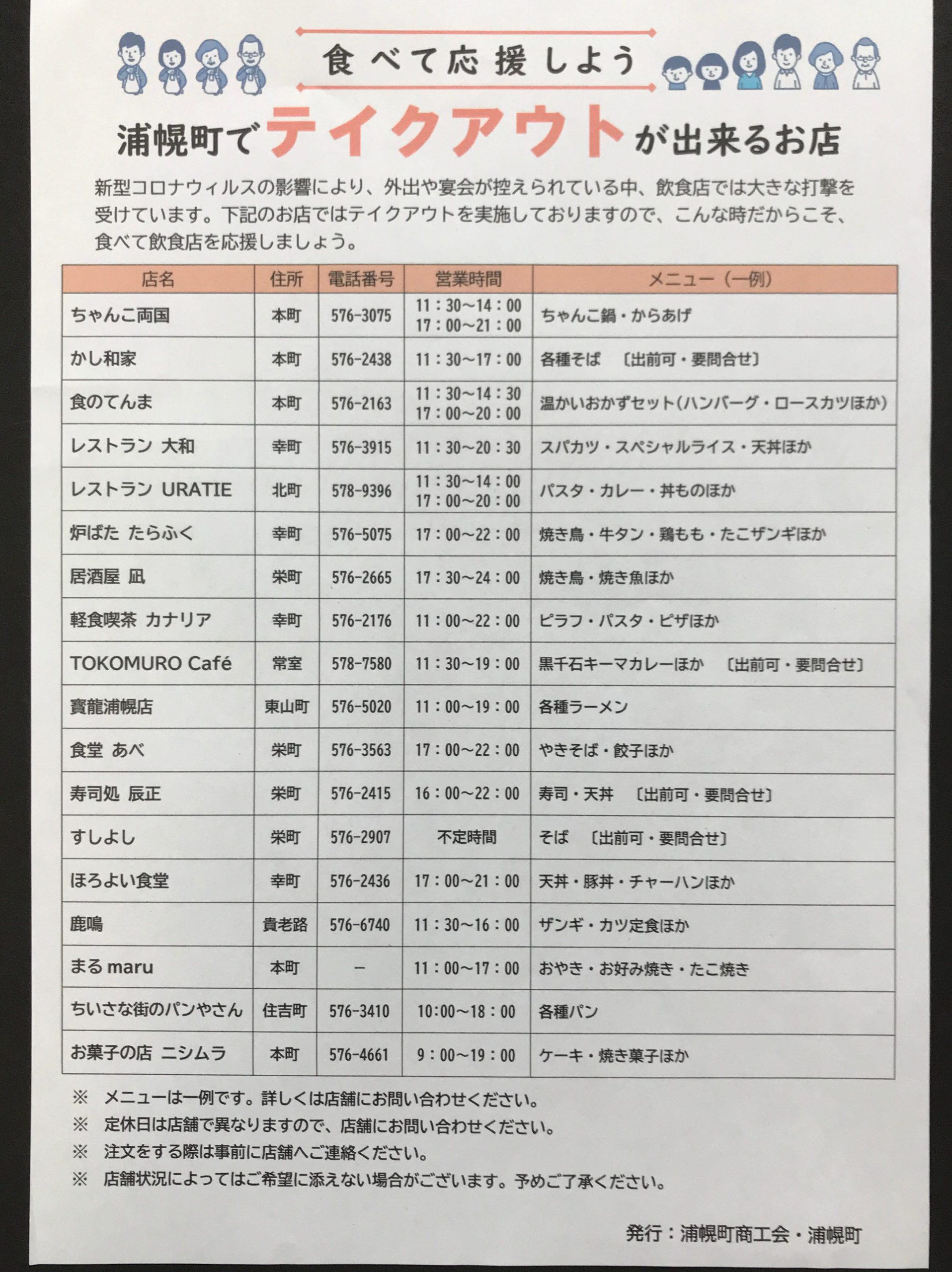

To prevent the spread of the infection, many Christian churches canceled their Sunday services and masses. The Catholic Church in Japan has established the “Prayer for the World Suffering from the New Coronavirus Pandemic” as a prayer text, and performs this prayer at every Sunday Mass.

It is known that, in fact, not many things from people’s lives during the time of the Spanish flu have been preserved. In contrast, museums in Europe and the UK have been quick to collect COVID-related materials during the current pandemic. In Japan, too, efforts to document the age of COVID-19 are spreading across the country, not only in museums but also in the fields of libraries and archives.

I think it is crucial to understand how many museums, libraries, and archives are currently collecting COVID-related materials. We have received fragmentary information about the situation in Hokkaido, but we still do not know the whole story. Going forward, I feel that it will be necessary to network with other institutions and sort out the gaps and unevenness in which materials are collected, across which regions, and by whom.

(Makoto MOCHIDA)

[1] Kido, Rie (2020). 『不登校新聞』のコロナ関係記事に見る「休校による不利益」の不可視性 [The invisibility of “disadvantages due to temporary school closures” in COVID-related articles of the Futoko Shimbun]. Gendai Shiso 48(10): 73-81.

[2] Ishikawa, Naoaki (2012). 「今」を記録する地域博物館 [Community museums that record the ‘now’]. Museum Studies 47(9): 27-30.

[3] Endo, Tetsuo (2019). おれの「食の考現学」[My ‘modernology of food’]. Gendai Shiso 47(9): 71-77.

[4] Public Relations Committee, The Japanese Psychological Association (2020). “Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19: How to stop the xenophobia that’s spreading along with the coronavirus.” https://psych.or.jp/special/ covid19/combating_bias_and_stigma/

[5] For example, the Japanese Journal of Clinical Psychology 20(4), 緊急特集:コロナウイルス時代のカウンセリング [Urgent special issue: Counseling in the COVID-19 era].