June 4, 2021

An Art Museum in the COVID-19 Pandemic Situation: A Case of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Masahiro Shino

Director,

Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Infectious disease control in chronological order

It was on January 15, 2020 that the first case of an infectious disease caused by the new coronavirus, which is believed to have originated in Wuhan, China, was discovered in Japan. At the time, we, at the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, were holding an exhibition of the museum’s collection and deposited items. Unlike large-scale feature exhibitions, the percentage of visitors from overseas, especially from Asian countries, tends to be slightly higher for collection exhibitions.

On January 24, the reception and surveillance staff were required to wear masks. Five days later, on the 29th, the first case of infection in Osaka Prefecture was finally confirmed. The same day, we installed antiseptic solutions in the museum’s restrooms. However, although we were aware that an appropriate response might be necessary, based on our previous experience with SARS and MARS, we did not expect the situation to become as serious as it is now until around February 6, when the Japanese government imposed restrictions on entry into Japan from mainland China. The first organizational action by the Administrative Agency for Osaka City Museums (the “Agency”), the local incorporated administrative agency that operates our museum, was taken on February 10.

The Agency issued a press release stating while five museums and one office (the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, the Osaka Museum of Natural History, the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, the Osaka Science Museum, the Osaka Museum of History, and the preparation office for the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka) managed by the Agency would act in concert for the time being and cancel events including lectures, but exhibitions would be held as usual.

Consequently, gallery talks by curators in charge of a collection exhibition at the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts were cancelled. At the same time, the 6th Reorganized New Nitten, the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition, Osaka Exhibition (hosted by the Executive Committee of the Nitten Osaka Exhibition) opened as scheduled on February 22, but with no commentary on the works by the artists, so the exhibition was somewhat scaled down compared to the usual ones.

As the serious characteristics of the new coronavirus as an infectious disease gradually spread through various media and the sources of infection were pointed out to be specific groups or places called “clusters,” art galleries began to consider taking unconventional measures and that they should deal with the situation with a special sense of urgency.

It was when the National Governors’ Association issued an “urgent statement to curb the spread of the new coronavirus infection” on February 25 that the situation changed dramatically. At an emergency meeting of the Agency held on February 27, representatives from each museum reported on the current situation and exchanged opinions on future actions. In the afternoon of the same day, it was decided that all the museums would close temporarily from February 29. In addition to closing of the 6th Reorganized New Nitten, Osaka Exhibition after only six days, we decided to suspend all activities at our museum, including a public exhibition held in the basement exhibition room by art groups and the adjacent Art Research Institute, from the 29th and send the museum into temporary closure.

The situation was like a tunnel with no way out, as we could not foresee what would happen in the future and when the museum could reopen. At that time, however, I think most of us at the museum were still optimistic that it would reopen with the new fiscal year in April or by the Golden Week holidays at the latest. Because the museum went into temporary closure during scheduled exhibition periods, we quickly decided to refund the admission tickets for the Nitten exhibition and the venue rental fee for the groups using the basement exhibition room.

At the same time, we were instructed by the Agency to take a “customer-oriented approach,” so we staffed the main entrance to provide information for visitors who were unaware of the temporary closure. Then, on March 12, the Executive Committee discussed what to do with the Nitten exhibition, deciding to bring it to an early finish without waiting for March 22, its scheduled end, and sent out notifications accordingly.

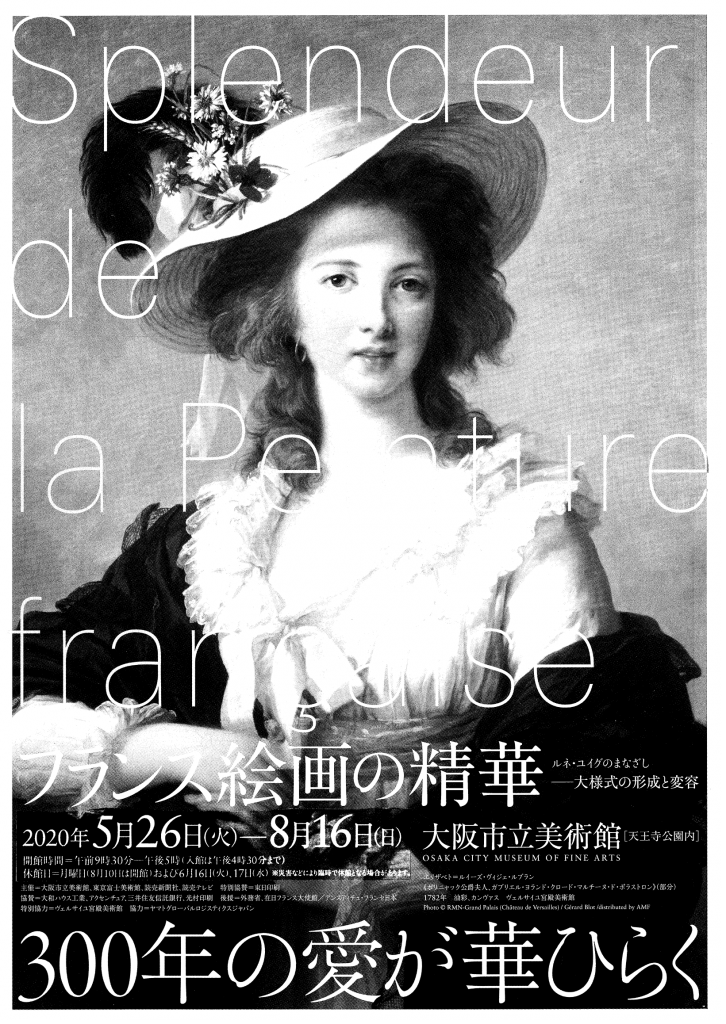

On April 7, after reports that the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games would be postponed and the death of a celebrity from a new coronavirus infection, the government declared a state of emergency (effective originally until May 6, and later extended). A feature exhibition entitled “The Splendor of French Paintings: 300 Years of Love in Full Bloom” (hosted by the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, the Yomiuri Shimbun, Yomiuri Telecasting Corporation, and the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum) was scheduled to open on April 11 but postponed indefinitely with the state of emergency, along with the opening ceremony and preview that had been cancelled earlier. Over 700,000 flyers had been produced, and the initial goal was to attract 200,000 viewers, but we were forced to go back to the drawing board.

Fortunately, we were the final venue for the exhibition, which had traveled through the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum and the Kyushu National Museum. The 66th All Kansai Exhibition, a public exhibition (organized by the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts and the Yomiuri Shimbun), scheduled to open in June, and the “Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou” exhibition (organized by the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts and the Yomiuri Shimbun), which was scheduled to open in August, were respectively cancelled and postponed. In addition, due to mutual travel restrictions, works borrowed from 20 famous museums in Europe, including the National Gallery of Scotland, the British Museum, the Louvre Museum, the Musée d’Orsay, and the Gemäldegalerie, could not be returned.

As a result, we, the organizer, began to look for ways to extend the exhibition period and resume the exhibition. In order to avoid complications in the chain of command and confusion about information, a single point of contact was set up at the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, which made inquiries to the respective owners and negotiated extensions of loans. Museums in Europe with ongoing lockdowns were forced to keep their staff at home, and the Musée d’Orsay, for example, needed the approval of its board of directors to transfer works. However, we were able to get permission from all the art galleries for loan extensions until the end of August thanks to our long relationship of trust with them.

Normally, according to international convention, staff of the art galleries that own works accompany the works as couriers even when the works travel within Japan. This time, though, Japanese staff took over the removal and transportation of the works from the Kyushu National Museum to Osaka, and the unpacking, display, removal, and return of the works were all carried out without a courier—a series of unusual situations I had never experienced personally.

Nevertheless, we faced an unexpected obstacle in opening preparations, namely securing masks and antiseptic solutions. In the first place, before the corona crisis, there was no need for art galleries to purchase large quantities of these materials. We had no access to them, and of course, they were not available in stores. Fortunately, we were able to procure necessary materials such as antiseptic solutions, masks, and plastic gloves through the feature exhibition executive committee and the Agency.

In addition, Tennoji Park (also known as “Ten-Shiba”), which usually attracts its largest number of visitors in a year during the spring vacation to Golden Week holidays, was quiet due to the spread of remote work and voluntary store closures. Also, the Agency established a rule for a “special leave system,” aiming to have fewer than 50% of employees report to work based on activity restrictions during the declared state of emergency, so such an unusual time stretched on through the spring of 2020.

The state of emergency declaration, which was once extended, was decided to be lifted in Osaka on May 21. Based on this, the Agency held a meeting and decided to open the museums by the beginning of June. At about the same time, the Japan Association of Museums announced the “Guidelines for Preventing the Spread of the New Coronavirus Infection in Museums.” Based on the guidelines, the executive committee set a new exhibition period from May 26 to August 16 for “The Splendor of French Paintings,” which had been postponed.

The Art Research Institute also resumed its activities on June 1 by securing social distance and setting some restrictions, but the basement exhibition room, where public exhibitions are held by art groups, saw a series of cancellations and only resumed with the 58th Gugenten Exhibition on August 4.

“The Splendor of French Paintings” opened 45 days later than originally planned after a series of preparations to introduce an unprecedented, new style of art appreciation. It was supported by the use of acrylic boards and plastic curtains to prevent droplets from spreading, thermography, and foot-shaped plates for people waiting in lines to keep physical distance, as well as a capacity setting (300 people) to limit the number of visitors in order to avoid crowding. None of these measured existed before the suspension of activities at the end of February.

In addition to the above, visitors were asked to submit “health check sheets” on top of temperature checks and mask wearing when entering the museum. After confirming the flow of the temperature check, reception, and viewing at the press preview on the 25th (the day before the opening), we were ready for the first day, the 26th, when 30 eagerly waiting people turned out before the door opened. In the end, 352 people came to the feature exhibition and 124 to the collection exhibition. Although the numbers were smaller than at usual large-scale feature exhibitions, we were able to conclude the first day smoothly.

We were particularly grateful that visitors proactively talked to our staff. There were abundant compliments such as, “Thank you for opening the museum,” “I realized the value of everyday life where I can experience something extraordinary (an exhibition),” and “Thank you to the staff for their preparation.”

Normally, organizers of such blockbuster large-scale feature exhibitions would focus on how to increase profits. But with the common expenses already paid and the expenses for publicity materials, construction of the venue, and air conditioning and surveillance for the Osaka venue already paid, we kept a close eye on the project with the peculiar goal of “how to reduce the deficit.”

To give an example, in response to the change and extension of the exhibition period, we made full use of the various newspaper and television media that gathered for the exhibition to publicize the exhibition. At the same time, since there was no budget to rework and print new posters and flyers, stickers indicating that the exhibition period had changed were printed separately for the 50,000 flyers remaining at the art gallery, and everybody pitched in to attach these stickers in spare moments during their normal work. Despite being a large museum in an urban area, our museum does not have a generous budget, and the principle is to do everything we can on our own.

The number of senior citizens who used to visit our art gallery decreased, suggesting a fear of going out in crowded places including public transportation and an atmosphere of prudence and self-restraint. In addition, the rainy season was unusually long. Also, as the number of infected people in Osaka Prefecture started to increase again in late July, the rise in the number of visitors slowed down. Nevertheless, numbers increased in August when the final day was approaching, and in the end, 60,031 people visited the exhibition in its 71 days.

Learning from the infectious disease disaster

It is interesting to note that when I “observed” the viewing attitudes of visitors in exhibition rooms right after the exhibition opened, it was remarkable that everyone kept a relatively large distance from others to the point of being nervous, and quickly moved on to the next work when someone approached the work they were looking at. However, in the final days of the exhibition, it became crowded, and the “density” of the pre-corona period emerged. Even so, I frequently witnessed people spontaneously giving each other what little space they had, bowing silently to each other when their shoulders touched, and expressing their consideration for each other. After all, it is the common sense of citizens that should be trusted.

I would like to emphasize that no infections occurred among those involved in the exhibition or visitors. This is thanks to all the companies that participated in the executive committee, as well as all the companies and people cooperating for the exhibition, that we were able to successfully close “The Splendor of French Paintings” under such unprecedented conditions. I feel that the same result would not have been achieved with any one of them missing. Once again, I would like to express my gratitude to everyone involved.

Although exhibitions are one of the derivative forms of a museum’s mission of “making things available to the public,” they are also occasions to collectively express the will of various stakeholders in the museum, such as other museums that own works, collectors, and the media, and this aspect of the business should not be overlooked.

In this sense, “the show must go on,” and museums must always keep their doors open, no matter what difficulties may arise.

In both the East and the West, art galleries and museums have historically been safe places. Examples are abundant. When a large number of disaster victims poured into the mountain of Ueno immediately after the Great Kanto Earthquake, the staff of the Imperial Museum (now the Tokyo National Museum) accepted them, dug simple toilets in the garden, and worked hard to prepare food for them. Even during the last World War, art galleries in Europe remained open. In some cases, concerts were held in lobbies and exhibition rooms amid shelling. This was to remind citizens of the sense of comfort.

These memories seem to have been passed on, and 25 years ago when the Great Hanshin Earthquake struck, one art gallery in a relatively undamaged area of the disaster-stricken region did not rush to close its doors, but instead nonchalantly kept them open. In the 1980s, the Metropolitan Museum of Art maintained a steady stream of visitors while New York was struggling with recession and deteriorating public order.

Art galleries and museums are devices that preserve not only materials but also the memories of people who visit them. That is why, in this time of corona crisis, we are taking all possible measures to prevent the infectious disease, thereby hoping that citizens and visitors will remember what they learned, found, and were moved by in museums before the corona crisis arrived.

On a personal note, I experienced the Great Hanshin Earthquake in 1995 when working for the Otani Memorial Art Museum in Nishinomiya City. While the city was in a state of utter devastation, I spent most of my time doing restoration work and caring for affected citizens. About a month later, an organized disaster-survey team visited us, and one of the members was a conservator from the U.S. She gave us a book, praising our measures to protect the artifacts from damage in a typical American way, saying, “Good job!” The title of the book was “Steal this handbook.” It had been compiled by a group of conservators of art galleries in the American Midwest, and listed the risks facing museums and how to deal with them. It listed not only natural disasters such as earthquakes, lightning and floods, but also man-made disasters such as terrorism, theft, fire, nuclear disasters and disease. The list was full of items on the relationship between art galleries and disasters that I could not have imagined at the time.

In that sense, we may have a lot to learn from the recent global outbreak of the new coronavirus. Fortunately, unlike earthquakes or terrorist attacks that occur suddenly, things have changed relatively slowly and have been easier to deal with. There have also been multiple guidelines produced to handle the situation.

Although there is a relatively high level of concern about earthquakes and floods, which are prominent in this country, as a pressing issue, measures to control infectious diseases, not to mention the future of international cultural exchange, should be worked out on a case-by-case basis. These measures should take into account the conditions of each museum’s location, the structure of the building, the characteristics of “public” projects such as exhibitions and lectures, the staff structure, budgetary measures, and the number of visitors, in order to implement risk management in the field. Moreover, the guidelines should not be understood as a set of golden rules, but rather as something to apply flexibly according to the situation.

(Masahiro Shino)

* Collaborator: Tadashi Tsukada, General Affairs Section Chief of our museum