May 28, 2021

Attention was taken to ancient documents of the Edo era: the times of the COVID-19 and Yogen no tori

Akihiro Morihara

Chief Curator, Yamanashi Prefectural Museum

1. A “prophetic bird” lands on our museum

Who could have foreseen how the world would turn out in 2020? The arrival of the “time of COVID-19” has had a significant impact on a regional museum such as the Yamanashi Prefectural Museum in Yamanashi Prefecture. Despite the situation, one item from our museum collection has attracted nationwide attention–the “Yogen no tori” (Figure 1). This prophetic bird is an imaginary creature depicted in a Japanese diary from more than a century ago. It has since “soared” high above the museum, leading a museum at a loss from the pandemic towards a brighter future. In this essay, I would like to explain the background to how early modern historical materials that have not gained much attention until now came to attract the public, even having a knock-on effect on the local economy. I will set out my views on this situation and remind the reader of what to keep in mind when communicating information.

2. What is the “Yogen no tori”?

In 1858, a cholera epidemic broke out in Nagasaki in southwestern Japan, arriving in Edo (now Tokyo) in July. By the end of July, the epidemic had spread to Kofu Castle in Kai Province, which was then under the direct control of the Edo Shogunate.

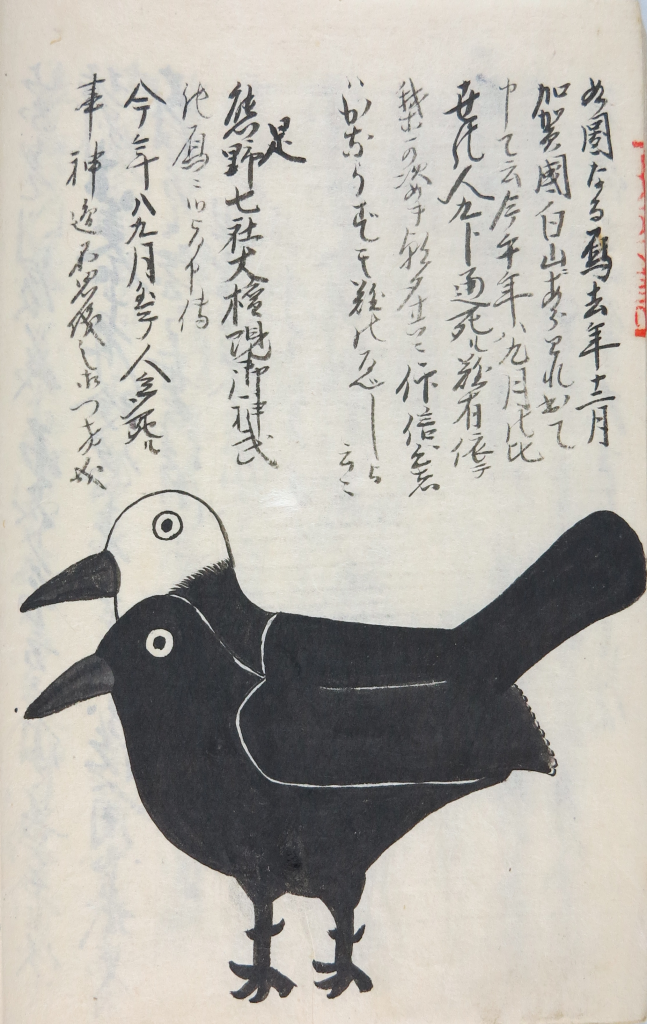

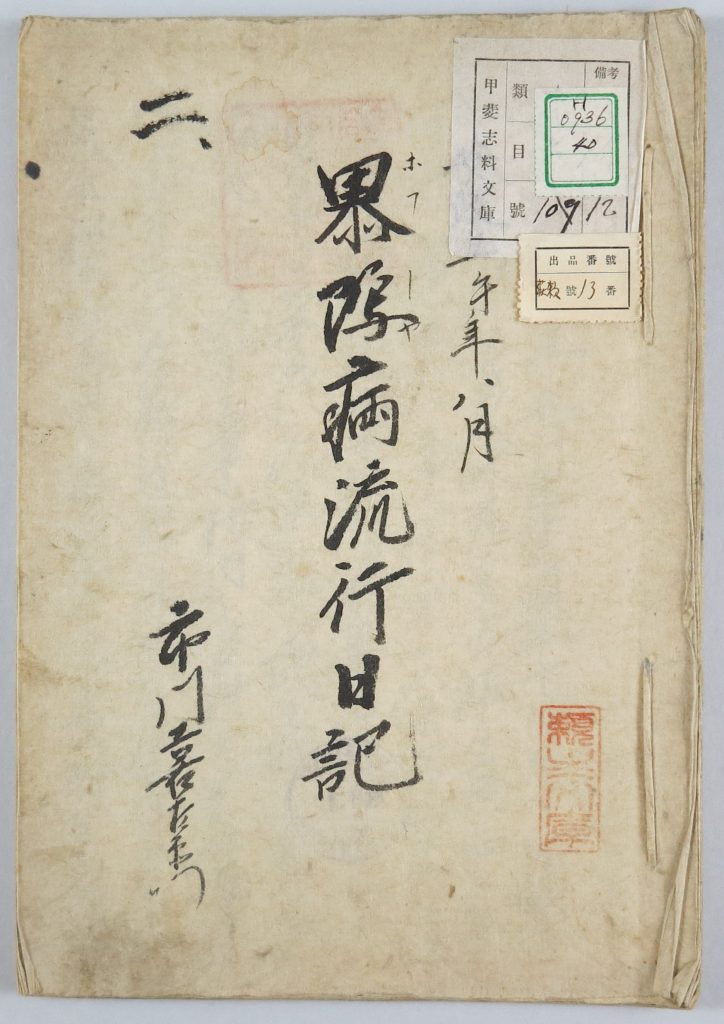

Kizaemon, the head of Ichikawa Village located in what is now the city of Yamanashi in eastern Japan, witnessed the epidemic with his own eyes and kept a record of his experiences. It has been left to us as the “Journal of a Cholera Epidemic” (Figure 2). In the Journal, Kizaemon introduces a rumor he heard during a visit to Kofu, accompanied by an illustration and an explanation written in Edo-era Japanese. A modern translation of his words might read something like this.

“A bird similar to one in this illustration is said to have appeared in Kaga Province in December last year and spoken the following message. ‘A tragedy will befall your people, of whom nine in ten will die in August and September next year. Those of you who pray to us morning and night and truly believe, shall be spared from this disaster.’

This bird was said to be an incarnation of the great power of the Kumano Gongen deity, which is renowned for its virtue and authority. Then, in August and September this year, large numbers of people died. It is truly God’s power and a strange prophecy.”

(Yamanashi Prefectural Museum)

It seems likely that Kizaemon had heard rumors of a tale made up to distract people who were feeling anxious about the epidemic rather than about anything that happened in Kizaemon’s area. However, faced with the threat of COVID-19 in modern times, I’m sure we can all fully appreciate his sentiment.

3. Before the “Yogen no tori” began to soar

The “Journal of a Cholera Epidemic” forms part of the Raiseibunko collection (approximately 4,000 items), one of the collections of early-modern history held by the Yamanashi Prefectural Museum. The collection is well-known among historical researchers in Yamanashi Prefecture and by curators of our museum. The Journal has displayed on public in past exhibitions. However, because no name was recorded for the bird shown in the artifact, it came to be known simply as the Yogen no tori, or the “prophetic bird.” However, the bird was not widely known or used much by the museum.

The bird started to attract renewed attention only after a burst of nationwide enthusiasm (brought on by the spread of COVID-19) for a sea monster called Amabie (Shimbun Collection Pictures, Main Library, Kyoto University, 1846) from the historical province of Higo. In no time at all, news of the Amabie artifact had spread across the internet via Social media and other online means. It had become widely known by people of all ages, genders, and nationalities, and even used to sell products. Seeing this, a curator in art history at Yamanashi Prefectural Museum tweeted the bird explaining that the journal entry had mentioned a “prophetic creature that helped people to escape infectious disease,” similar to Amabie. The tweet was posted on April 3, 2020, and immediately started to be retweeted. Incredibly, it had reached more than 10,000 ‘likes’ just one week after the original post.

The mass media reported the situation around mid-April. At the same time, the bird led to many requests from businesses. The museum allowed the image to be used for merchandising. Usually, our museum charges a fee for using artifacts for commercial purposes (60 USD per item). However, in response to the rush of inquiries, members of the museum began to express that we should not be charging a fee to use this artifact during the pandemic. After several discussions with Yamanashi Prefectural Office and the financial authorities, and thanks to the wise judgment of the prefectural governor, it was decided to grant a special exception to “exempt businesses located inside Yamanashi Prefecture from fees for using the artifact.”

After we posted the usage fee exemption on the Yamanashi Prefectural Museum website, we received a rush of applications and inquiries between late April and early May from businesses that had suffered a huge economic hit from the emergency declaration. The impact was such that staff responsible for handling applications could not to keep up with the administrative work. The unique situation faced in Yamanashi Prefecture, where tourism is a key industry, could be seen from the types of businesses that applied to use the image: businesses that made and sold souvenirs from the prefecture (for confectionary packages and designs), as well as the local wine, sake and fruit juice producers (for labels and wrapping paper), and the jewelry industry (for jewelry design). It became clear that industries in the prefecture were doing everything they could to survive the challenging situation. We also received many applications from shrines and temples, where charms and “shuin” seal stamps had given visitors.

4. COVID-19 measures at Yamanashi Prefectural Museum and the impact of the Yogen no tori

As the spread of COVID-19 became increasingly serious, Yamanashi Prefectural Museum announced on February 21, 2020, that events with people gathering together, such as seminars and hands-on events, would be canceled for the foreseeable future. On February 28, a further announcement was made to suspend the permanent exhibitions, prohibit the viewing of the collection, and postpone the upcoming spring exhibition. As the pandemic continued to spread throughout Japan, the museum announced temporary closure from April 2 through to the end of May, and all planned exhibitions were cancelled. As a result, the museum, which would normally be busy with visitors during the spring tourism season, fell quiet. In addition to examining how to prevent infections and respond to the new situation as we prepared for reopening, we continued to provide an online program for hands-on experiences and history lectures. It was during April and May – the “closed spring” that could perhaps be described as the most challenging time of all – when the bird flew down to us from above before soaring back high into the sky. Unable to do any face-to-face work with visitors, the museum had started to become very inward-looking, but the bird played the role of connecting us with the outside world. What’s more, when it was difficult for people to understand the importance of a museum, the bird played the role of a “spokesperson” for us.

On May 22, 2020, when the government had lifted the emergency declaration and society showed signs of returning to normality and recovering, the museum finally reopened, with restrictions (limited entry to the museum depending on the conditions for lifting the emergency declaration). Along with the reopening, we held an exhibition of the original artifact of the “Journal of a Cholera Epidemic.” The bird’s popularity helped us to avoid a sharp fall in visitor numbers. We hold an exhibition using the donated products bearing the bird’s image and displayed as many as possible of the pictures and craft items sent to us from across Japan.

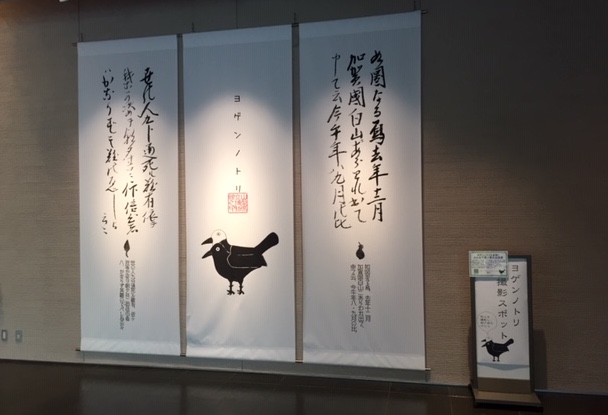

Today, visitors have continued to take commemorative photographs in the photo area, which was created by printing materials on a banner with a large printer (Figure 5). Some of our visitors even pray to it. Whenever I come across a scene like that, I cannot help but hope that the pandemic will end as soon as possible.

5. The impact of using Yogen no tori

Most historical materials do not have a major economic impact. However, the Yogen no tori has surely had a significant, even if the small, economic impact on the local economy thanks to the publicity and free use of the image. For example, the wine industry had struggled terribly due to slumping consumption brought on by the closures of bars and restaurants. However, we received the following comments from members of the industry. “The Yogen no tori saved us” and “I am so glad the museum keeps hold of historical artifacts.”

We also had new experiences, including people who asked if they could make donations to help preserve artifacts at the museum. Visitors have commented on how people have fought infectious diseases in the past and asked if we have any similar artifacts. The increased interest in local history led to calls for us to place a higher value on the history of infectious disease. The Yogen no tori case had the effect of spreading the message far and wide that “taking care to preserve history will help protect future society and generations.” This has worked well with a project that our museum launched at an early stage to collect COVID-19-related materials (such as masks and posters notifying the cancellation of events). The bird has had many different explosive effects, but these could perhaps be summarized as follows:

(1) it has shown a wide range of people the potential that historical artifacts have for stimulating the economy and revitalizing regions;

(2) it has shown the value of historical artifacts for modern society, not just as a way of looking back at the past; and

(3) it has shown that some historical artifacts can ease people’s anxiety and suffering.

6. Tips for effective communication and the ongoing story

The fact that the Yogen no tori became so widely known was not something that anyone had predicted, similar to how COVID-19 arrived. It seems unlikely that this situation would not have come about without social media, a powerful way of communication. The time between tweeting and having the flood of requests to use the image was incredibly short, and it would have been easy to become overwhelmed if we mishandled the situation. Thanks to the repeated investigations and research we had already carried out into the value and significance of our artifacts, we were able to respond in a calm-headed way.

Looking ahead, we need to keep in mind that online communication can invite an explosive response and that we might need to handle the reaction at a speed that is hard to imagine. It is essential to continue steadily carrying out investigations and research on our artifacts, which could be the foundation for a museum. The next point might be slightly unusual, but we also need to remember to register trademarks for the designs themselves, including things like artifact names and nicknames. As a general rule, museums should not create opportunities for the commercial monopolization of historical heritage, which is a common property that should be shared with the public.

Around six months have now passed since we first let the world know about the Yogen no tori, but there has been no end to the requests for its use. I want our museum to fulfill its role of watching over our “Yogen no tori” as it soars high up into the sky above while providing a safe home for it to come down and rest its wings whenever it feels the need. The day when our “Prophetic Bird” can retire from its current role cannot come soon enough.

(Akihiro Morihara)