February 4, 2022

New Possibilities for Art Museums by Collection and Digital Transformation

[2022.2.4]

Hitoshi KOBAYASHI

Chief Curator

The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka

The Pandemic and Art Museum

The pandemic has inevitably brought about significant changes to people and society, and art museums are no exception. The vacant exhibition room unraveled that a museum is only complete when visitors enjoy viewing the artworks on display. However, the fact of the matter is that a collection must reside in a museum. I was reminded of the quintessence of a museum, which is to inherit a collection and utilize them comprehensively.

While museums were temporarily closed or unable to welcome visitors, online activities such as digitization, video distribution, and webinars suddenly increased. These activities gained traction with the societal trend of the “digital transformation,” with the pandemic as a major driving force. The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka (hereinafter referred to as the “Museum”) had steadily taken on digitalization since before the pandemic, so we were able to continue progressing, through trial and error, even during the coronavirus outbreak.

These efforts are not merely a temporary response to the pandemic but have important implications for the future of art museums. This article will introduce the Museum’s efforts, focusing on the digital transformation of art museums and the utilization of their collections, and explore the possibilities and prospects for the future of art museums amidst the continuing pandemic.

Images of Artworks for Museums

On March 26, 2021, the Museum released “The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka Open Data” in multiple languages (Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean) as part of a project supported by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (Image 1 and 2). There is a prominent movement within museums in Europe, the United States, and other Asian Countries to have an open databank for images of artifacts belonging to a collection. However, in Japan, the tradition of publishing images and collecting fees for their use is still dominant and difficult to overcome. In this context, the Museum is unique because it allows large-volume, high-resolution images to be used without application procedures. 1

Photograph by Shigeru NISHIKAWA

In most cases, many people come into contact with images (including video) of artworks through catalogs, books, magazines, videos, and more often than they do with actual artworks. It is clear that these images do not equate to the actual works, which is all the more the reason why images are an essential medium to convey the beauty of the works. The resolution of image-related equipment has progressed far beyond what it was a decade ago, thanks to the widespread use of ultra-high-definition video technologies such as 4K and 8K and the higher resolution of digital cameras and smartphone cameras. The Museum allows visitors to take photos of artworks in the exhibition rooms under certain conditions; however, the current mainstream method for interacting with the artworks is for visitors to take photos of their favorites with smartphones and post them onto social media.

In this context, now more than ever, regardless of the pandemic, art museums need to come up with innovative ways to enhance the “ability to view” artworks – in other words, to enhance the “resolution of the eyes” through the use of images and video as a means of broadening the scope of appreciation, improving accuracy, and deepening understanding. In this sense, the quality of the images produced by the museum is quite significant. The quality here does not only imply a high pixel count; more important is the resolution of color and textures. If you are a curator at an art museum, you may have experienced the difficulty of color proofing images for catalogs numerous times. With the abundance of image data on the web and print media such as books and magazines, the images provided and published by museums should exceed a certain quality and not resemble an image scanned from antique slide films.

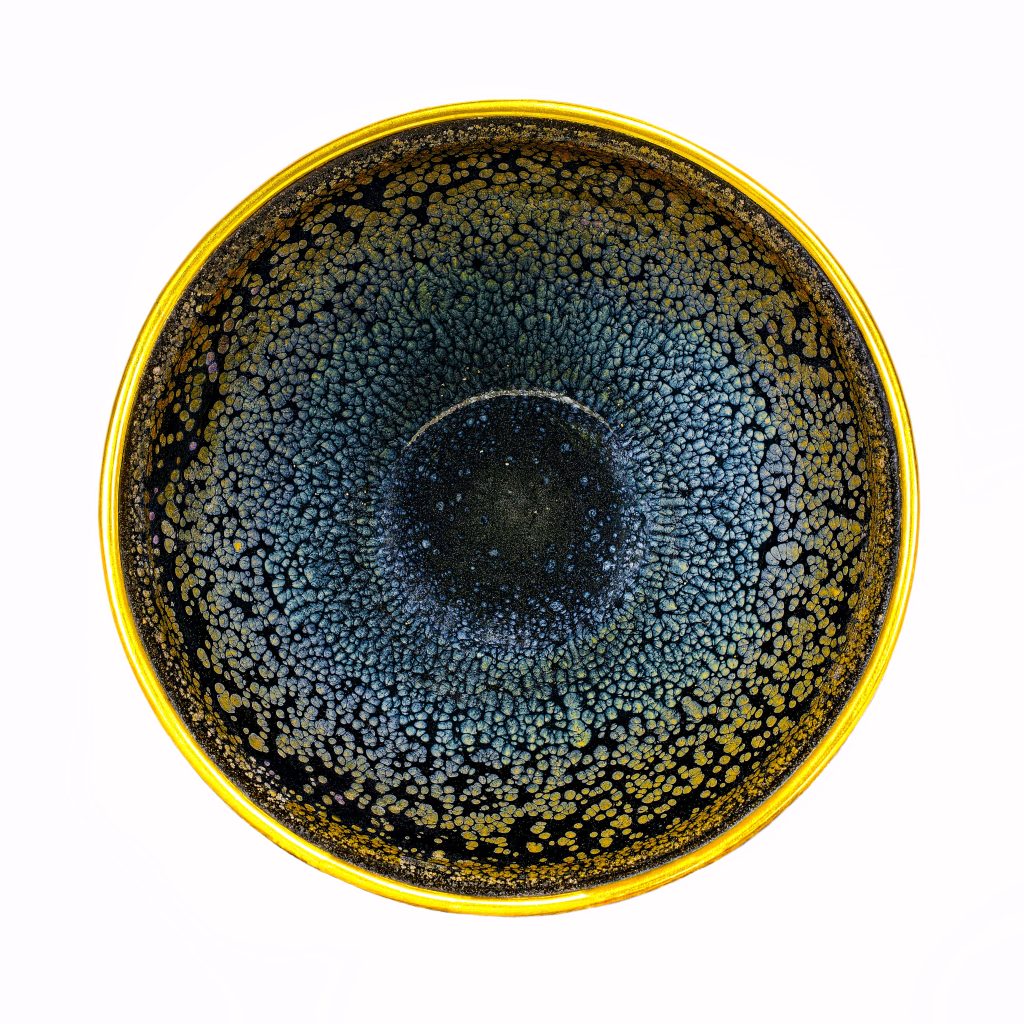

In 2020 during the coronavirus outbreak, the Museum held an exhibition from our collection, “Special Exhibition: Tenmoku―The Beauty of Chinese Black-Glazed Ware,” where I used equipment that excels in reproducing color and texture to create high-definition, high-resolution photographs. When I saw the image data of the National Treasure Yuteki Tenmoku (oil-spotted tenmoku tea bowl) for the first time, I was astounded – the brilliant color gradations, the texture of the mottled patterns of the oil drops, and the gold trim was unlike anything I had seen before (Image 3).

The catalog “Tenmoku—The Beauty of Chinese Black-Glazed Ware” (Chuokoron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2020) was printed using a broader color reproduction method to make the most of these luxuriously rich-colored images. In addition, printed images were placed next to the explanations of the exhibition (Image 4). Some visitors commented that as they took a closer look at the objects, they noticed a diversity of colors start to appear, and I shared the same experience.

The conventional images become insufficient after seeing such elevated images. Indeed, this is what it means to enhance one’s “resolution of the eyes.” What was initially an interest in this method of photography as a new approach to the study of artworks became the realization that such high-quality digital images open up new possibilities, not only for research but also for the appreciation of artworks. It was essential for the museum to provide images in high-volume data to maximize the experience and use of the expansive high information content since most of the images released as part of the Museum’s open data program were captured using this method.

Incorporating the latest technology is not the objective, neither is accepting any cutting-edge technology. The justification lies in whether it has the potential to be a valuable tool for museums for art appreciation, research, and education. It becomes imperative to flexibly and swiftly incorporate means conforming to the technological advances and generational changes.

Photograph by Shigeru NISHIKAWA

Art Museums in the Metaverse Era

The efforts to release and distribute digital images and video content, among other materials online are a means, not an end. To piece together these “points” into “lines” and expand furthermore into a “plane,” the Museum’s Open Data website linked to Japan Search, a national platform for aggregating metadata of digital resources of various fields, in September last year. In addition, we launched an initiation project and research to convert artworks into 3D data.

The enthusiasm surrounding the “metaverse,” a simulated virtual environment, reminds us that we have entered a new echelon of the digital age. There is anticipation in the widespread utilization of images from museums and other digitalized resources in such a platform. During the temporary closure, there was a call for museums to release 3D records of their exhibition rooms, in which the Museum partook. In the future, it will be a prerequisite for systems to allow various forms of user interaction both virtually and in reality, which is evidenced by the participation of many museums worldwide in Nintendo’s game software, “Animal Crossing: New Horizons,” and its global success.

The merit and possibility of an art museum in a simulated virtual environment is its ability to go beyond the reproduction of a real space and create a new exhibition space without physical limitations. In other words, the collection can be arranged and displayed to its fullest extent, and users will be able to create their own exhibitions. Since the previous year, the Museum has explored the potential of virtual exhibitions and their convenience for curators by way of simulating a series of exhibitions or interacting with people from around the globe.

In particular, I believe that the art museum will demonstrate its potential in education and learning more than ever before. Recently, as exemplified by the STEAM Education, promoted by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, artistic ideas have been applied to business, and virtual exhibitions have a high affinity for cross-disciplinary learning that fosters the ability to discover and solve problems in the real world. The appreciation of artworks such as ceramics is not limited to sight but involves all five senses. Complementary substitution and expansion of the senses in a virtual reality environment is the latest much-anticipated field of development that achieves further social inclusion in art museums.

An art museum centers around their collection of artworks, and the digital transformation did not take away the value and necessity of encountering artworks in the flesh, as the pandemic revealed interaction among people, whether through a screen or in-person, is valued differently. Preceding the “Virtual Expo” in the Master Plan for the Expo 2025, Osaka, Kansai, Japan, a city-linked metaverse named “Virtual Osaka” has been unveiled. In this metaverse era, the simulated virtual environment opens doors for undertaking various activities that utilize the museum collection.

Utilizing the Collection

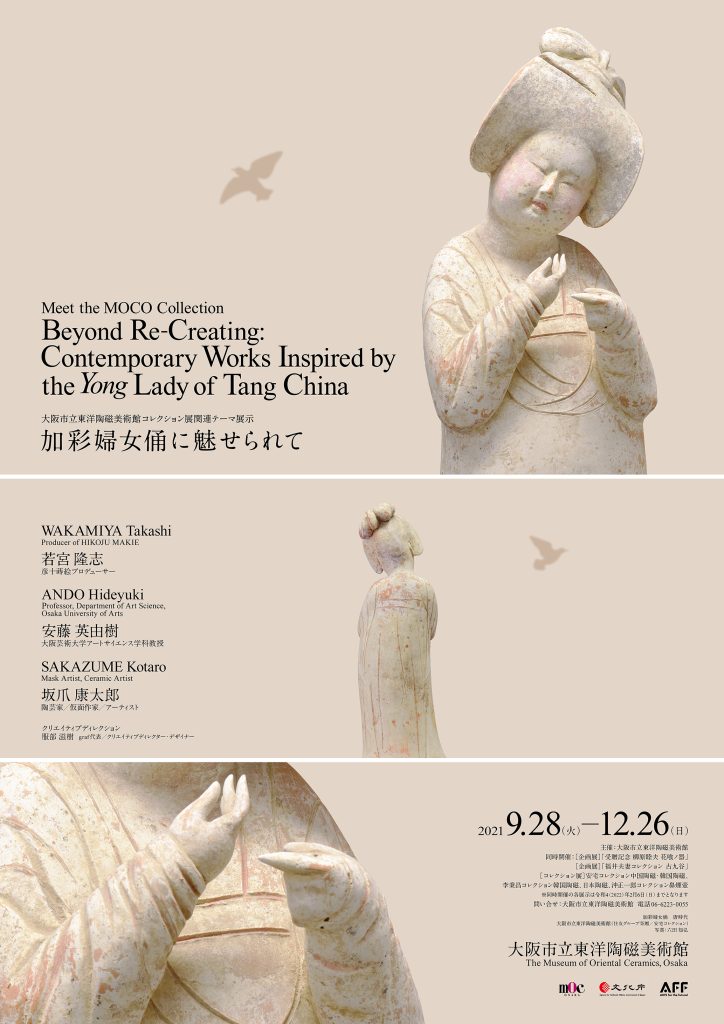

For the art museum, inheriting the collection means adopting it in the present and connecting it to the future. The exhibition “Meet the MOCO Collection Beyond Re-Creating: Contemporary Works Inspired by the Yong Lady of Tang China” (September 28 – December 26, 2021) was held as a subsidized project of the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ “ARTS for the future!” in 2021 (Image 5). Focusing on a representative work from the ATAKA Collection, ” FIGURINE OF A LADY” from China’s Tang Dynasty, three contemporary artists from different genres used this work as a motif for their new creations.

This exhibition proved to be a prime opportunity to showcase the possibilities of utilizing the Museum collection by including artists from non-ceramic genres, such as lacquerware and media art, and exhibited interactive media art using the latest technology such as 3D data and 3D printers (Image 6).

The response from visitors was very positive: “It was so exciting and moving to see my favorite figurine from a different angle and perspective.” “It was invigorating. I would love to see more exhibitions like this in the future.” and “It was an interesting new approach.” When a diverse crowd gathers to view a collection exhibition, it instills life back into the collection and raises its value. I was reminded of the importance of sharing this contemporary significance with others. The sustainability of museums depends on becoming an institution where people can meet, connect, and give birth to new ideas with artwork at its core.

The Possibilities of Art Museums

The pandemic has threatened the existence of art museums, whose goal is to provide in-person encounters to artworks. In fact, it is not limited to the pandemic; there are always a variety of threats and risks, ranging from natural disasters and climate change to war and terrorism. This is why I was reminded of the importance of museums and the collections housed there. The ICOM Kyoto 2019 taught us that museums are not immune to social and environmental issues and there is significance in addressing various social issues.

Living through the pandemic has only strengthened our belief in this concept. There were limitations on the existence of a “venue” even before the pandemic, as some people, regardless of their interests, cannot visit museums as frequently as they would like due to their conditions or environment, and probably constitute the majority compared to actual museum visitors.

In that regard, the digitalization and progression of the internet have led to creating and expanding a new type of “venue” for museums that transcends such limitations and restrictions. The fact remains that museums are venues where people can encounter collections, whether in reality or virtually, and we must be relentless in our search and constantly be willing to adapt to new environments and generations to protect and entrust the collections and heritage of museums.

(Hitoshi KOBAYASHI)

Visit The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka Website