June 11, 2021

Administration and Future Issues of an Aquarium Which Lost Inbound Visitors by the COVID-19 Expansion

Keiichi SATO

General Manager, Aquarium Business Department, Okinawa Churashima Foundation (Deputy Director-General, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium

1. Background of Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium

Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium’s predecessor was the government-operated Okinawa Expo Aquarium, which opened in September 1976. Okinawa Expo Aquarium was part of a project to redevelop a marine life park that was a national exhibit of the Okinawa International Ocean Exposition of 1975. It was remodeled into the new aquarium in 2002. Since then, it has become a facility that drives Okinawa Prefecture’s tourist economy with a steadily growing number of visitors. Its economic effect in northern Okinawa is estimated to be 65.0 billion yen (source: Okinawa General Bureau, FY2014). In recent years, it has attracted more visitors than any other aquarium in Japan, with more than 3 million people a year.

In addition to its identity as a tourist facility, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium is home to the “Okinawa Churashima Research Center,” which raises and studies rare marine organisms of the world. It has produced numerous achievements of international significance, particularly through its research on sharks. The Okinawa Churashima Foundation, which is the center’s designated administrator, has a staff of researchers that includes eleven PhDs. It actively engages in research studies and public awareness, particularly through its Animal Research Laboratory.

The COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2020 had a major impact on Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium’s circumstances. Operating revenue decreased due to restrictions on activities that resulted from calls on the public to refrain from going outdoors and lower visitor numbers. This presented a challenge in terms of business continuation, as it affected not only the aquarium’s administration and finances but also research and education activities that are funded by its revenues. On the other hand, there were also many instances where emergency preparations functioned effectively and in which the aquarium’s attractiveness and influence were clearly evident. Such instances pointed to the possibility of new advancements for the future. In this paper, I would like to examine the challenges that arose from the pandemic and the aquarium’s response and extract lessons for the future.

2. Visitors to Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium: Composition and Characteristics

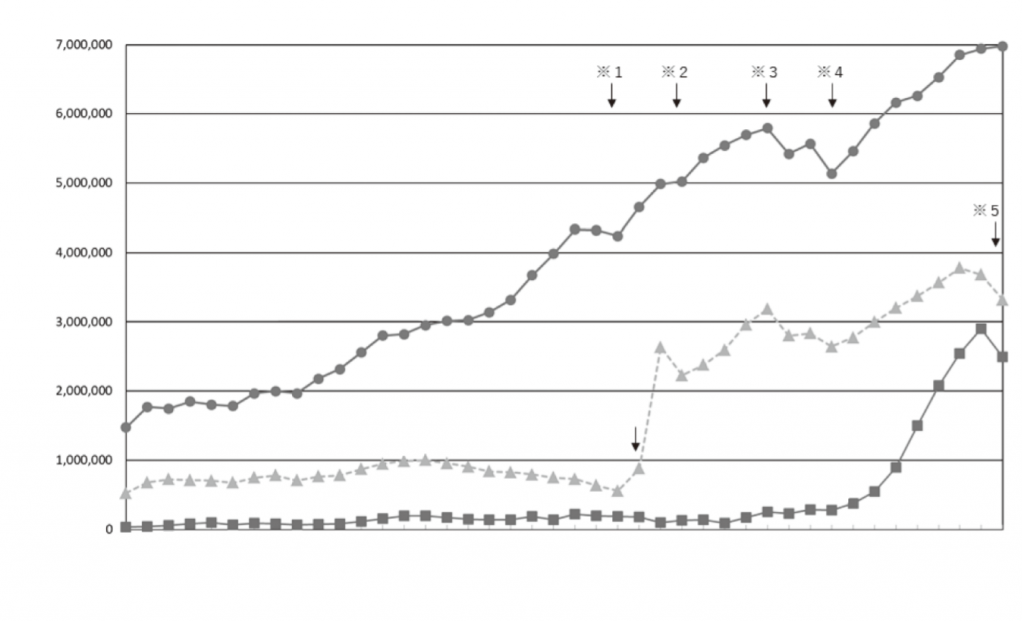

Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium is one of Okinawa’s leading tourist destinations. At the time that it opened in FY2002, the annual number of tourists visiting Okinawa Prefecture was 4.89 million. The next year, FY2003, that number reached about 5.12 million for a year-on-year increase of 4.7%. This demonstrates how the aquarium served to drive a boom in Okinawa tourism at that time. When the aquarium opened, most of the tourists coming to Okinawa were Japanese. However, a surge in overseas (inbound) visitors began in 2013, and their share of all tourists entering Okinawa exceeded 30% in 2018. The number of aquarium visitors also increased year by year, reaching a record high of 3.78 million in FY2017. This growth was primarily supported by inbound tourists (Figure 1).

(●= domestic tourists, ■=international tourists; from tourism statistics of Okinawa Prefecture), and ▲=number of aquarium visitors)

Fiscal year 1978 to 2019)

*1: 9-11 terrorist attacks in New York (September 2001)

*2: SARS epidemic (2002-2003)

*3: Financial crisis of 2008 (2008) and novel influenza pandemic (2009)

*4: Great East Japan Earthquake (March 2011)

*5: Deteriorating Japan-ROK relations and COVID-19 pandemic (FY2019)

The aquarium routinely conducts a questionnaire survey and grasps visitor trends by analyzing its items. According to survey data for FY2019, 58% of aquarium visitors were domestic tourists (outside of Okinawa), 9.2% came from Okinawa Prefecture, and 32.8% were inbound tourists. Looking at inbound tourists by country, 90% came from the three countries of Taiwan (39.3%), China (mainland; 38.3%), and South Korea (12.2%). The shares for mainland China and “other countries” have been rising in recent years, and thus it is anticipated that nationalities will become more diversified. Additionally, it is predicted that the planned opening of a cruise ship terminal at Motobu Port will lead to increased visitor numbers and greater fluctuation in the nationality makeup.

3. Challenges in Attracting Tourists and Inbound Tourists to Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium: Composition and Characteristics

Greater numbers of inbound tourists each year have contributed significantly to higher numbers of tourists entering Okinawa Prefecture and the development of the prefecture’s tourism industry. Okinawa developed as a maritime nation, both geographically and historically. And, as is inscribed on the “Bridge of Nations Bell,” Okinawa has served as a bridge linking Asian nations through sea trade.

Returning to the topic of the aquarium, Japan’s zoos and aquaria are facing the prospect of decreasing visitors in the future as Japan’s birthrate falls and its society ages. Thus, attracting inbound tourism demand is important for administrative improvement aimed at securing the sustainable development of aquarium facilities into the future. Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium has attracted robust inbound tourism demand by promoting a language barrier-free environment based on five languages. Recently the aquarium has successfully captured a diverse range of visitors as the holiday seasons of various countries occur throughout the year. This has contributed greatly to the local economy. However, as the current COVID-19 makes clear, attracting inbound tourism entails some degree of unpredictable management risk.

A look at changes in the numbers of tourists entering Okinawa Prefecture and aquarium visitors shows that, although there have been year-to-year increases overall, some “small waves” have occurred (Figure 1). In the years during which slowdowns or decreases in aquarium visitor growth occurred (indicated by asterisks), the main causes were the 9-11 terrorist attacks in New York (2001), the SARS outbreak (2002-2003), the financial crisis of 2008 (2008), a novel influenza pandemic (2009), the Great East Japan Earthquake (2011), and a period of sour Japan-South Korea relations (2019). Of these, the 9-11 terrorist attacks had a particularly severe impact on tourism, as many group and school tours to Okinawa, which hosts numerous U.S. military bases, were canceled. An aquarium located far from the mainland can only be reached by aircraft and is thus greatly affected by typhoons, epidemics, terrorist attacks, international circumstances, and domestic disasters. For this reason, attracting tourists, and especially inbound tourists, is attractive but should be assumed to involve risk. Very recently, in 2019, friction between South Korea and Japan led to a dramatic decrease in South Korean visitors to Okinawa and the aquarium beginning in July. Their number fell to almost zero in September.

The foundation entrusted with operating the aquarium has implemented measures envisioning an array of emergencies based on past experience, including disasters, international conflicts, and epidemics. One example is its acceptance of registration as a research organization of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in 2014, which led to its proactive introduction of Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research and other external funds. Moreover, in the area of aquarium management, the foundation formulated a business continuity plan (BCP) and executed measures in anticipation of unforeseen circumstances, including preparing infection control manuals, stockpiling emergency supplies, and supplying information through multilingual apps. However, the effects of the COVID-19 far exceeded what was envisioned.

4. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Aquarium’s Response

At the end of December 2019, infections from a mysterious pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, China. With the Chinese New Year approaching at the end of January 2020, the aquarium notified its employees of measures to control infections on January 16 in anticipation of a large number of Chinese visitors. Although the true nature of the “mysterious pneumonia” was still unknown at that point, we reviewed our infection control manuals and checked our stock of hygienic supplies based on past experience. Moreover, we instructed our nurses and others to review aid manuals and instructed staff members to wear masks and practice thorough hand-washing and hand sanitation in preparation for the arrival of many tourists from mainland China. Although the number of visitors from mainland China was slightly lower than expected during the Chinese New Year, the aquarium staff had their hands full remaining vigilant against an unknown virus in an anxious atmosphere.

COVID-19 cases began increasing from February 2020, and calls by Okinawa Prefecture to refrain from going outdoors led the aquarium to close temporarily on three occasions: March 2 to March 15, April 7 to May 31, and August 2 to September 5. The aquarium is a facility that handles living animals and therefore must avoid operational shutdowns. Accordingly, we employed a split-team work system, subdivided tasks, and endeavored to control the number of people in high-risk contact when cases of infection occurred.

In March 2020, Okinawa Prefectural Government reconsidered its policy for holding events. This led us to reopen on March 16, ahead of other aquariums throughout Japan, which remained closed. Because of our experience with SARS and epidemics of new strains of influenza and measles, we prepared infection control manuals and stockpiled thermography devices, masks, sanitizers, hypochlorous acid solution, and other supplies. I believe such precautionary measures and experiences ultimately contributed significantly to the aquarium’s reopening. At the time of the reopening, we independently studied countermeasures in line with the government’s basic action policy, and we decided to take temperatures with thermography devices at the entrance, make hand sanitizers available, execute measures to prevent crowding, and strengthen ventilation with building air conditioners and by leaving emergency doors open. Looking particularly at ventilation, we recalculated the capacity of existing equipment and secured ventilation exceeding 30 m3/h per person with air conditioners that bring in air from outside. We then constantly monitored CO2 concentration and operated a forced ventilation system for about fifteen minutes whenever the concentration started rising. We operated the forced ventilation system based on changes in monitored CO2 concentration values and actual increases or decreases in visitor numbers.

Left: top page (the congestion rate is shown in real time on the upper left)

Right: example of aquarium guidance in Chinese

Additionally, we asked visitors to install the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium app (Figure 2) on their devices before entering the facility so that we could notify them quickly if a case of contact infection occurred inside. The app includes an aquarium guide and fish identification function in five basic languages for inbound tourists. It can therefore compensate for incomplete explanations that are a side effect of program cancellation and for the unavailability of rented audio guides. From its beginning, the app has been designed to help disperse peak congestion times, as congestion rates are displayed in real time at the top of both the app and aquarium website. While originally intended for dealing with inbound tourists, the app’s value has increased significantly through its usefulness in coping with COVID-19.

We also took additional steps to prevent zoonotic infections in light of our status as a facility that handles animals. These steps, which included disinfecting shoe soles and suspending programs that allowed visitors to touch animals, were taken with particular concern for marine mammals, which may be susceptible to COVID-19 infections.

Due to the measures described above, no infections from visitors have been recorded among the aquarium staff and no cluster infections have occurred within the facility as of September 5. This is despite the fact that we have welcomed visitors from many infected regions. Nonetheless, it has become that there are limits to infection countermeasures that are based on “requests for cooperation” that are nonbinding and lack a legal basis. In particular, there were instances and complaints involving failure to get cooperation with mask-wearing and temperature-taking. Thus, it may be necessary for the future to develop not only industry guidelines for dealing with infectious diseases but also laws and ordinances concerning facility operation and management.

5. Looking Ahead to the Post-COVID World

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are unpredictable, making it difficult to get a view of the post-pandemic world. Museums, which maintain their facilities with usage fees, and especially zoos and aquaria, which have living exhibits, now face major challenges in terms of their financial circumstances. Moreover, as infections continue unabated, they also face challenges in terms of business continuation, and they must protect their employees and avoid becoming sources of infection. Okinawa Prefecture and Okinawa Convention & Visitors Bureau (OCVB) are currently taking steps toward diversifying inbound tourism (which is heavily dependent on East Asia), attracting extended-stay tourism, increasing average spending per tourist, and sustainable environment-friendly tourism. For its part, the aquarium has responded to diverse needs by, for example, accepting MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions) and promoting facility use for nighttime events to meet local demands. Instead of simply promoting expansion-based tourism, we will likely need to “improve quality” by enhancing exhibits and programs, responding to various use formats, and the like. We will likewise need to develop a “risk-resistant” management system by upgrading its crisis management capabilities.

We have experienced and learned much as a result of the enormous COVID-19 pandemic, an event outside living memory. While many of these experiences and lessons are mentioned in a negative light, I believe we have a duty to record what we can do and what we notice now for the future. Excluding finance-related aspects, which are universal, I would like to summarize the points we have learned in terms of facility management. They are (1) although the aquarium stopped functioning as a tourist facility, it continued to function as a museum; (2) a business continuity plan and preparations for the threat of new infectious diseases are important; (3) the effectiveness and limitations of digital technology, and the importance and significance of practical education; and (4) the roles that Okinawa and Churaumi Aquarium have as bases for interaction with neighboring countries.

Heretofore, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium’s educational activities have been based mainly on face-to-face learning and physical contact. In particular, our touch-based approach to biological observation for the visually impaired has been praised as a leading initiative. While we had to change or suspend many educational programs to control infections, one of the things we discovered we can do during the aquarium’s closure is livestream content to hospitals and holding remote lessons for children’s hospital wards and special needs schools. After learning that many children were completely cut off from the outside and suffered anxiety as a result of COVID-19 countermeasures, we actively implemented such initiatives in cooperation with general hospitals and special needs schools in the prefecture and the rest of the country.

Although the aquarium stopped functioning as a tourist destination, it maintained its educational functions as a museum. Indeed, it is safe to say that the new initiatives I just described became possible precisely because the facility had become an “empty aquarium.” Online tours via the internet for the general public and “hybrid” tourism through digital devices will undoubtedly become important tourism content. Having said that, however, our role as an aquarium is not to serve as a virtual space, but rather to provide a place to physically experience real things through seeing and touching. I believe mutual understanding and international goodwill deepen when people gather in the aquarium, engage in conversation, and increase their interaction. Today, with inbound tourism drastically decreased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, my sincere hope is that, as Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium overcomes language barriers and increases opportunities for sharing emotion, the day will come when we again have a place for international exchange in the community.

(Keiichi Sato)