May 21, 2021

Introduction of the special issue “Museums during the Pandemic”

Kazuomi NISHIKIORI

Director of Tokyo Sea Life Park,

Editorial Committee Member of Museum Studies

1. Introduction

As a member of the editorial committee in charge of planning special issues, I would first like to apologize for the change in the theme of this one. Initially, this November 2020 issue was scheduled to feature the “Mold Problems in Museums.” I would like to apologize to contributors who were preparing for this topic and to readers who were looking forward to it. We appreciate your understanding. The editorial committee of Museum Studies agreed that it was necessary to make a special issue on the museums facing the new coronavirus infection at this point in 2020, even if it meant a sudden change of plan and announced the change in the August issue.

Next, I would like to mention something that may be considered inappropriate. Due to the global pandemic, the infection began to spread in Japan too around February 2020, causing many cases of infection and deaths. As of mid-September 2020, the number of infected people around the world exceeded 30 million, more than 940,000 people had died, and there is still no end in sight. Overseas travel has been restricted to prevent the infection from spreading, and inbound visitors (overseas tourists visiting Japan), numbering over 30 million last year, have vanished. The pandemic is a medical and public health problem and a tremendous disaster that seriously affects people’s lives and the economy.

On the other hand, this pandemic may have practically forced the world to carry out a grand social experiment in various fields. It may have been something more than just negative effects stemming from this pandemic. Think back to just a few months before the spread of the disease. For example, what has become of the issue of overtourism and the acknowledged need for, but lack of, progress in digitalization?

Many museums were closed for extended periods of time due to reducing the risk of infection. This was a situation that had never been experienced before, except in times of war. This special issue has been written by people from different types of museums. Each museum will have experienced its own unique circumstances depending on whether it is a history museum, folk museum, science museum, art gallery, zoo, aquarium, insectarium, railroad museum, or any other kind. Art, culture, and sports are not absolutely necessary for survival but are an essential element of what it is to be human. While it is the risk of infection that needs to be reduced, not education, culture, or the arts. In just a month or two we had to deal with a plethora of new issues in the practical settings of museums amid all the confusion. What should we do about masks? Should we use face shields instead? Do we have enough disinfecting alcohol? Should we introduce thermography?

We should avoid non-essential outings, but does that include museum visits? Travel restrictions are in place, so how should we transport artworks? How should we decide whether to cancel an event? How should we protect our animals from infection? How will we maintain social distance? What is the difference between telework and remote work? Should we have meetings via Zoom? What is that in the first place?

The revenue-generating departments are shrinking, and expenditure on infection control is increasing. Even when closed, zoos and other facilities that keep animals need to take care of them as usual. What is the significance of a museum’s existence amid this turbulent time? Shouldn’t the BCP (Business Continuity Plan) have anticipated this kind of situation? What does a sustainable museum mean? Questions kept cropping up in my mind.

2. Articles comprising this special issue

The special issue brings you a collection of discussions that deserve widespread attention at the moment. These articles were written amid the pandemic of 2020, when words such as “non-essential,” “social distance,” “PCR testing,” “new lifestyle,” “nesting,” and “XX at home” were commonplace. These articles would have been difficult to write a year ago and probably even a year from now.

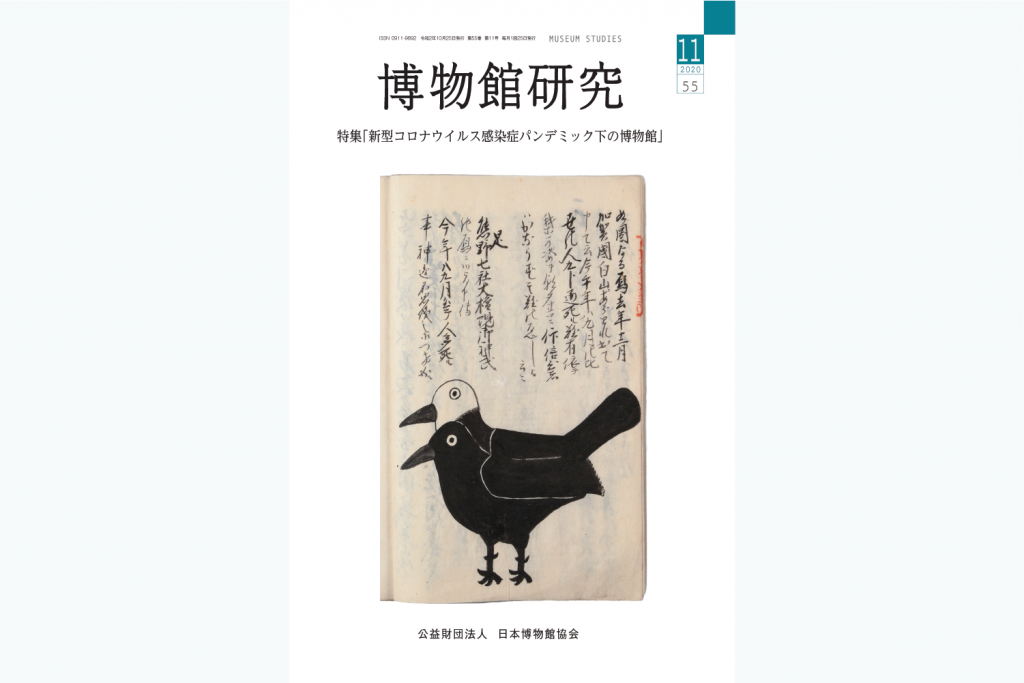

Mr. Akihiro Morihara (Yamanashi Prefectural Museum) introduces the bird called “yogen no tori,” which became famous overnight along with Amabie, a monster with a legend to ward off plagues. The bird is an example of an ancient document that drew attention. He also introduced its economic effect and ways to get the word out and provided points to consider regarding design.

Mr. Masahiro Shino (Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts) presents his museum’s infection control measures in chronological order as a specific case study, discussing the circumstances surrounding the unusual postponement of a feature exhibition and the lessons to be learned from it.

Mr. Keiichi Sato (Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium, which used to attract more than three million visitors a year) tells of what he saw was the museum function of the aquarium when tourism declined due to the loss of inbound visitors.

How did science museums communicate the pandemic? Ms. Hiromi Takao (Tamarokuto Science Center) reiterates the importance and difficulty of science communication and the original mission of science museums.

At this very moment, flyers and other materials related to the pandemic are disappearing. Mr. Makoto Mochida (Historical Museum of Urahoro) discusses the need to collect materials that are difficult to preserve from the perspective of local activities.

Mr. Kojiro Hirose (National Museum of Ethnology) now dares to mention the significance of touching. He emphasizes that universal museums will connect the world. What has happened is remembered and recorded. However, what should have been done and what should have happened during the lost time will not be remembered or recorded because it did not happen.

We should consider the implications of “recording lost performances” as pointed out by Mr. Ryuki Goto (Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, Waseda University).

The special contribution by Mr. Liu Yang (Museum of Nankai University, China) provides a valuable perspective on Chinese museums from a person involved with them.

In addition to the opening essay, seven feature articles, and one special contribution, this issue also includes content related to the pandemic in the “Branch Information” section (Mr. Yuki Hosomomi, Itabashi Historical Museum), the “From the Japan Association of Museums” section, and the “Museum Clips” section.

We have also discussed the coronavirus pandemic in past issues: the view on holding various cultural events (Agency for Cultural Affairs) in the April issue; the link between a feature exhibition and the new coronavirus crisis (Ms. Aya Koikawa, Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History) in the May issue; the Guidelines for Preventing the Spread of the New Coronavirus Infection in Cultural Facilities (Agency for Cultural Affairs) and the Guidelines for Preventing the Spread of the New Coronavirus Infection in Museums (Japan Association of Museums) in the June issue; “Beware of the Flu” (Ms. Hiromi Inagaki, Naito Museum of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry) in the July issue; the project to prevent infectious diseases in cultural facilities (Japan Association of Museums) in the August issue; the need for museum policies that respond to the paradigm shift in the corona crisis (Mr. Yuji Kurihara, Kyoto National Museum), the home museum (Ms. Mizuki Shibuya, Hokkaido Museum) in the September issue (the latter also in the October issue); and what museums are asking in the new normal (Ms. Izumi Odaka, Newspark), and using social media during a museum closure (Ms. Misato Shomura, the Museum of Fine Arts, Gifu).

We hope you will take a look at them along with the feature articles in this issue. During this pandemic, people have experienced a number of instances where what used to be normal is no longer so in a short period of time.

The same is true for us, the museum staff. Some people may feel a sense of resignation that things will only follow a predestined path. However, the loss and limitation we have faced have reminded us that we understand things with our physicality. The kind of cultural richness that museums have been protecting, connecting, and passing on was one of them. Under such circumstances, museums, as cultural institutions, should stand in defense and endure the disaster until it passes and continue to take practical actions to connect cultures.

What kind of society should be rebuilt after the pandemic, how museums should be involved in this process, and whether they can or cannot. None of the articles in this special issue represents the ideal form of museums in the future that everyone agrees on. However, as people involved in the sudden change of the world in 2020, the writers present points of view that emerged from the range of ongoing efforts they made. In the “with-corona” world, aren’t museums also looking for concise expressions that will illuminate the future and attract attention?

The articles in this special issue do not offer any expressions that respond to such a request. Rather than giving a bird’s-eye view or an analytical perspective, they vividly show the hardships, anguish, and frustration of actual museums. And yet, they are looking toward the future of museums. That is how I feel. Museums are sure to keep moving ahead, and I am certain that there are discussions in this issue that we will fully understand when we read them again a year from now.

3. What museums have lost

One thing that has progressed rapidly in museums during the pandemic is digitalization. Online meetings using Zoom have become the norm. The use of social media such as Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook has greatly increased. Furthermore, video streaming and live broadcasts on YouTube have become popular. There has been a wide uptake of cashless and touchless systems and a rapid shift toward chatbots (automatic conversations) using AI (artificial intelligence) and online pre-entry reservation systems. However, as in other industries, progress varies greatly. Remote-controlled robots are being tried out for museum tours, and VR (virtual reality) and AR (augmented reality) are being introduced in museums one after another.

Time seems to have fast-forwarded several years during the last few months. Zoom, for example, has a recording function that makes it possible to analyze dozens of participants’ facial expressions over time with automatic recognition and analysis of smiles and other facial expressions on the video. Detailed analysis of the atmosphere of workshops, lectures, seminars, and the participants’ level of attention is also possible. Some people may have thought about the difference between the degree of communication and the sense of communication, which they were not usually aware of. Although the speaker may feel that the message is understood better in direct communication (sense of communication), the actual degree of communication may be higher online.

I also found some advantages in online communication in that it is surprisingly easy to introduce and convenient. It can transcend space and is suitable for gaining knowledge efficiently. However, whether the rapid progress of digitalization will lead to a digital transformation that can create a new culture and even transform society may depend on how it can appeal to people’s emotions, which are different from the measures of convenience and efficiency.

While there were some gains, some things that had been there at museums were lost without us even noticing. What did we lose? For one thing, “coincidence” has disappeared. It was only by being there that we could make discoveries from a visit to see something else or notice for the first time the merits of something we were not interested in before when we stopped by a section without a purpose. The article on serendipity by Ms. Izumi Odaka in last month’s issue (October 2020) is beneficial for understanding this point. A museum that was open every day was always live, and there would inevitably be some unplanned moments when unexpected things would happen.

On the other hand, content that is not live but was thought out efficiently and well has no room for unplanned moments. What you want to convey is efficiently communicated without excesses or deficiencies and within a given time frame. People, however, may not like things that are impeccable. In the real museums that people love, there was room for coincidence.

Something else we lost is “time.” This is when feature exhibitions would have been held, lectures and guided tours would have been given, and exhibitions would have been viewed. Even if we are able to hold the same exhibitions six months or a year from now, that lost time is irretrievable. Even if museums themselves do not disappear, the time in 2020 when activities would have taken place in museums has been lost.

And yet another thing that has been lost is the “liveliness” of museums as places. It is not just that there are a lot of people, but also that there is a pleasantly noisy atmosphere, or that there are people having small conversations here and there after viewing exhibits. Even if the number of visitors increases, I doubt we will be able to regain the kind of bustle where people engage in such lively conversations anytime soon. Even when the pandemic is over, I am afraid some things may not return to normal immediately.

4. Museums in the Anthropocene

We have been building our civilization in the Holocene epoch in terms of geological age. Now, we are said to be already in a new era, the Anthropocene. Human activity has become greater and more widespread than ever before, leaving unique traces in the geology of the earth’s surface. Plastics, pure aluminum, and artificial radioactive materials have formed layers in the geology of the entire planet. Carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and other substances derived from human activities have increased in the atmosphere and are changing the climate.

COVID-19, which has appeared in the Anthropocene, has spread to humans through infection with a virus transmitted between wild animals. Infectious diseases that affect humans and other animal species are called zoonoses, and COVID-19 is one of them. In the past few decades, AIDS, SARS, and Ebola hemorrhagic fever have spread in the same way. Humans continue to modify and invade the natural environment, including reducing wildlife habitats through large-scale development in the Anthropocene world. The opportunities for humans to contact with unknown pathogens will increase, and new infectious diseases are expected to appear one after another in the future.

Although COVID-19 is a major disaster, some believe that it is only the beginning of the threat of the Anthropocene compared to the effects of climate change and oceanic changes that will be inevitable if greenhouse gas emissions keep on rising. How many times have we heard phrases such as “once in a few decades” and “record high” for heavy rains and high temperatures this year? Abnormalities such as floods and frequent wildfires caused by high temperatures are becoming commonplace in the Anthropocene.

Last year (2019), American teenage singer-songwriter Billie Eilish sang of “hills burning in California.” This year, California again experienced massive wildfires, and San Francisco’s sky turned dark and eerily red even in the daytime. Both the climate crisis and the pandemic are realities of the Anthropocene. If a once-in-a-century pandemic were to occur every few years, our current society would be unsustainable.

Humanity has probably reached a fork in the road. Human history is ending, and civilization is ending— what we see before us is a fork in the road of this magnitude. The museum professionals, who are the recorders, keepers, and guardians of civilization, are now living together in an anxious age, seeing that “the end of civilization” written on the wall. Even if we survive one disaster, the crisis will come back in a different form.

Predictions abound in this angst-ridden world. Predictions of the future have the effect of encouraging us to think about how we will respond to those predictions. Still, they also have another effect: If the predicted future is undesirable, we can change it. The only people who can do that are those of us who live in the present. At that time, learning from history and thinking about the present will give us power. Art can be a form of power. Yes, there are things that museums can do and should help with. The name of the song mentioned above by Billie Eilish is all the good girls go to hell.

5. Museums as cultural hubs

While writing this article in September 2020, I tried retracing my memory of what I was doing around the same time last year. In September 2019, ICOM General Conference was held in Kyoto. The conference was held in Japan for the first time with over 4,600 participants from 120 countries and regions around the world. There were discussions on how museums were preparing for disaster risks, but there was no discussion on the risk of infectious diseases forcing museums across the globe to close. The theme of ICOM Kyoto 2019 was “Museums as Cultural Hubs.” The final day’s resolution included “Commitment to the Concept ‘Museums as Cultural Hubs.” Once again, the theme of ICOM Kyoto and the resolution resonate heavily and strongly in my heart.

The feature articles in this issue report on the activities of various museums under the pandemic and contain essential concerns for the future of museums. However, only some of them are included this issue, we will continue to publish discussions on COVID-19 and museums in subsequent issues. We look forward to hearing the opinions of our readers.

(Kazuomi Nishikiori)